An Ascent with Xenophon

I first heard of Xenophon and Anabasis while at college, in Bl. John Henry Newman’s great book The Idea of a University. In this particular essay, Newman gives an illustration of a poor applicant for university studies by giving a dialogue between a student and a tutor. This student does indeed stumble through the interview, able to give a basic summary of events in Anabasis but unable to answer questions about the etymology of the title and its significance, basic Greek grammar, and other such things. What struck me, though, was that Newman assumed that even a poor student will have read Anabasis, among other works from the Classical world, and have some basic knowledge of Greek and Latin. Indeed, in the printed essay, Newman does not even transliterate Greek words; he merely assumes that anyone reading would know the Greek alphabet.

Yet, here I was, a year or two into university studies, and I was clearly far less competent than even this student Newman describes as “below par.” I knew no Greek at all, and the name of “Xenophon” was merely a foreign sound to me, though I was at least aware of the other authors Newman mentions in the passage.

Unfortunately, despite being a literature major, the rest of my education did not improve my situation. The only works of Classical literature I read were Homer’s The Odyssey and Ovid’s Metamophoses. The same professor who assigned those also assigned Aristotle’s Poetics, in the Loeb edition that included Longinus and Demetrius, who we also read. My only experience with Plato came, unexpectedly, in a course on science fiction and fantasy; the allegory of the cave was relevant to some story we read, I think only tangentially, but the professor told us that he wouldn’t let us go through college without at least some exposure to Plato. Some connoisseurs may scoff at genre fiction, and with reason, but I must give credit to this instructor who at least took his field seriously enough to look outside it on occasion.

One would hope that students would notice that they were not getting what they were paying for and insist on a better curriculum. Confucius once said that in a given village one may find a man as honourable and sincere as he, but none as fond of learning. Unfortunately, one may search a university campus and find no one fond of learning at all. Most of my classmates were there simply to get a degree, and I only met a couple others truly interested in literature. I was on my own, but between coursework, student organisations, and a job, I wasn’t willing to make the time to stop letting school get in the way of an education.

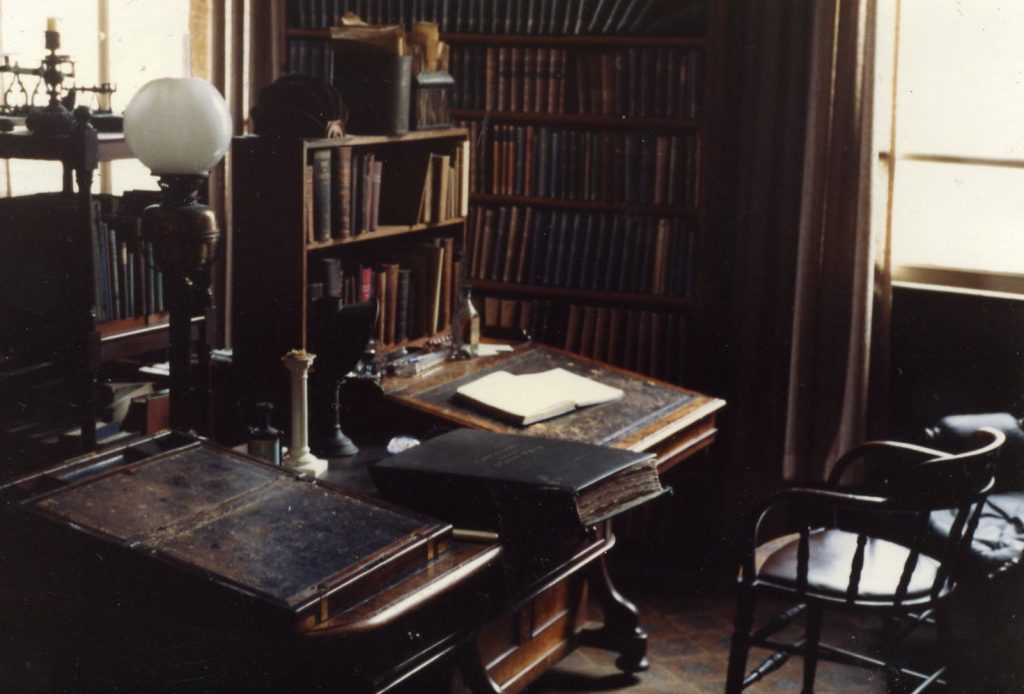

After graduation, I have indulged fully in my bibliophilia and surrounding myself with books. Just recently, I even got around to reading Anabasis, albeit in Robin Waterfield’s English translation (titled in his edition The Expedition of Cyrus, for those wanting to look it up). As I’ve been documenting on this blog, I’ve made some progress over the past year in bringing my knowledge of the Greeks closer to par, and since I finally made it to Xenophon, I thought I’d take another look at Cardinal Newman’s comments on his sub-par student. What, exactly, had gone wrong with this young man’s preparation for higher studies?

As it turns out, this guy was me.

Newman writes:

This young man had read the Anabasis, and had some general idea what the word meant; but he had no accurate knowledge how the word came to have its meaning, or of the history and geography implied in it. This being the case, it was useless, or rather hurtful, for a boy like him to amuse himself with running through Grote’s many volumes, or to cast his eye over Matthiæ’s minute criticisms. Indeed, this seems to have been Mr. Brown’s stumbling-block; he began by saying that he had read Demosthenes, Virgil, Juvenal, and I do not know how many other authors. Nothing is more common in an age like this, when books abound, than to fancy that the gratification of a love of reading is real study. Of course there are youths who shrink even from story books, and cannot be coaxed into getting through a tale of romance. Such Mr. Brown was not; but there are others, and I suppose he was in their number, who certainly have a taste for reading, but in whom it is little more than the result of mental restlessness and curiosity. Such minds cannot fix their gaze on one object for two seconds together; the very impulse which leads them to read at all, leads them to read on, and never to stay or hang over any one idea. The pleasurable excitement of reading what is new is their motive principle; and the imagination that they are doing something, and the boyish vanity which accompanies it, are their reward. Such youths often profess to like poetry, or to like history or biography; they are fond of lectures on certain of the physical sciences; or they may possibly have a real and true taste for natural history or other cognate subjects;—and so far they may be regarded with satisfaction; but on the other hand they profess that they do not like logic, they do not like algebra, they have no taste for mathematics; which only means that they do not like application, they do not like attention, they shrink from the effort and labour of thinking, and the process of true intellectual gymnastics. The consequence will be that, when they grow up, they may, if it so happen, be agreeable in conversation, they may be well informed in this or that department of knowledge, they may be what is called literary; but they will have no consistency, steadiness, or perseverance; they will not be able to make a telling speech, or to write a good letter, or to fling in debate a smart antagonist, unless so far as, now and then, mother-wit supplies a sudden capacity, which cannot be ordinarily counted on. They cannot state an argument or a question, or take a clear survey of a whole transaction, or give sensible and appropriate advice under difficulties, or do any of those things which inspire confidence and gain influence, which raise a man in life, and make him useful to his religion or his country.

Occasionally, I feel contented least with what I most enjoy, and recently I’ve started feeling less satisfaction from what I read. This comes and goes over time, and I’m sure that it’s partly a simple factor of what I happen to be reading. Recently, that’s been Longinus and Demetrius’s books on style and the sublime, and Xinzhong Yao’s An Introduction to Confucianism; the first two rather dry, and Yao’s, though interesting, not particularly deep, since it is intended as a textbook and a simple introduction to a larger topic. I think, though, that my largest problem is that I’m reading too much, too quickly, and “never […] stay or hang over any one idea.”

To be sure, I have gotten better at this over time. I annotate my books somewhat, and writing about them here certainly forces me to dwell on them. I’ve been especially careful about this with my posts on Plato. On the downside, I also feel pressure to get through books and their reviews quickly in order to get new material both on this blog and other outlets, where I’m afraid I’ve been a rather irregular contributor. Going the entire month of June without a post has weighed on me.

What I plan to do, then, is tap the brakes and stop worrying so much about my backlog of things to read. I may not become the man of one book who St. Thomas Aquinas feared, but will attempt to read with more depth and less breadth. How this will affect posts here, I can’t yet say.

In any case, please excuse this exercise in navel-gazing. I’d originally intended to write a review of Anabasis, but Cardinal Newman’s observations seemed more important at the moment. We’ll return to more regular, but I hope better, reviews next time.

Oh, right, and Xenophon is a good guy, and you should read his book. Just be sure to spend some time with it.