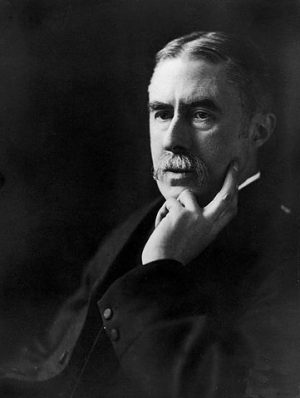

Today we’ll meet Mr. Thomas Campion, who was born in London in 1567 and lived to 1620. Yes, once again, there was just something about this era in English literature where it seems like every single Englishman couldn’t help but write fine poetry. Mr. Campion’s day job was physician, but he was also a songwriter and musical and literary theorist in addition to being a poet.

A few of our friends, like John Crowe Ransom, did write literary theory but we haven’t covered this much yet, so I think it may be interesting to spend a few moments looking at Mr. Campion’s Observations in the Art of English Poesie. Don’t worry, I won’t get into the nitty-gritty since even I find this type of thing a bit dry (see Aristotle). For most of the pamphlet he discusses the types of poetic metre and which are most apt for use in English, but he opens with an extended criticism of rhymed poetry. Now, today that may not seem like such a big deal, since the large majority of English poetry has been unrhymed, and often not even metrical, for decades now. At the time, though, it was the standard in English verse, and Mr. Campion notes, “whosoeuer shall by way of reprehension examine the imperfections of Rime must encounter with many glorious enemies, and those very expert and ready at their weapon, that can if neede be extempore (as they say) rime a man to death.” He keeps up the hot takes throughout the discussion, too, in a way that would make Ezra Pound proud. For instance, “the facilitie and popularitie of Rime creates as many Poets as a hot sommer flies.” This holds true even today to some extent; everyone who think they can rhyme a little, which isn’t terribly difficult, has likely produced a bad poem or two.