Fifteenth Friend: Walt Whitman, When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer

Last week we discussed Ezra Pound’s “Pact” with Walt Whitman, which turned out to be about as peaceable and long-lasting as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. This week, we’ll meet with Walt Whitman himself.

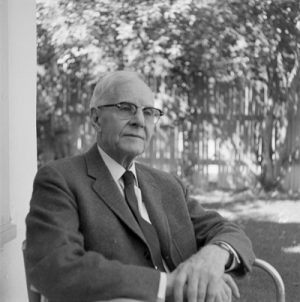

Mr. Whitman was born in 1819 and grew up in Brooklyn. Professionally, he struggled for most of his life both in his day jobs (editing newspapers and as a clerk for the Department of the Interior) and as a poet. Some of this was just bad luck, like one publisher going bankrupt at the start of the War Between the States, while others stemmed from the content of his poems; Ralph Waldo Emerson was a supporter of his, and he also became popular in England because of his reputation as a champion of the common man, but the first few editions of Leaves of Grass did not sell well and critics responded poorly to his use of free verse. Exacerbating matters were accusations of indecency in his poems, which is why he was dismissed from his post at the Department of the Interior, and in 1881 a Boston publisher stopped publication of Leaves of Grass thanks to the efforts of an outfit called the Society for the Suppression of Vice. The controversy did bring some attention to the book, though, and once he found a new publisher finally found some moderate financial success.