Today in the United States, we’re celebrating Thanksgiving, commemorating that well-known story of Native Americans helping out a bunch of proto-Yankee Puritans… Well, that was nice of them, I must give credit for that, but if the Natives had seen the future they may have followed the example of the friend we’re meeting today and done something far more laudable: not feeding Puritans, but fighting them.

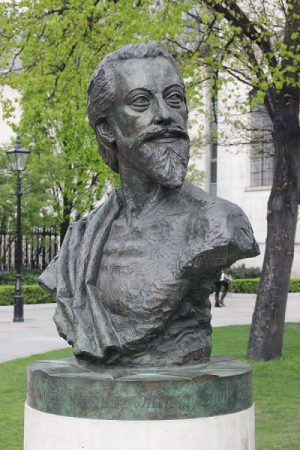

James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, is one of my favourite of the Cavalier poets. Part of the reason, of course, is his poetry; I especially like “My Dear and Only Love,” which is a good romantic poem in its own right, and the specific imagery he uses to describe a loyal relationship between husband and wife, monarchy, is apt but today has the added satisfaction of political incorrectness. He also, of course, supported the Royalist cause in the English Civil War. Interestingly, though, he was a Covenanter, and as such opposed King Charles I insofar as the King attempted to impose Anglican forms of worship on Scotland. However, he insisted throughout his life that he was both a Covenanter and loyal to the monarchy, and in 1644, with the Civil War underway, he was appointed lieutenant-general and won several victories in Scotland. Unfortunately, the Royalists lost, Charles I was martyred, and so Montrose fled to the Continent, but returned to Scotland in 1650 with a force of about 1,200 men. That invasion failed and he was ultimately captured and hanged.