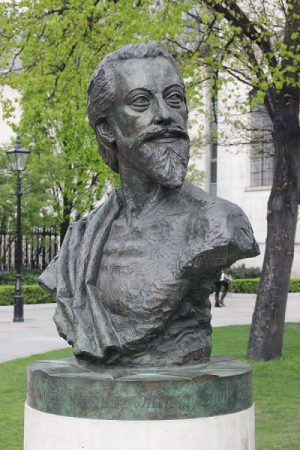

Third Friend: John Donne, "Holy Sonnets: Death, be not proud"

Our next acquaintance is with John Donne, who lived about a century before Alexander Pope, having been born in 1572 and passing away in 1631, and like Pope his family’s Catholic faith caused him some trouble early in his life. Interestingly, his mother was a direct descendent of St. Thomas More, and though he was able to study at Oxford and Cambridge, he couldn’t receive a degree there because his religion prevented him from swearing a required oath of allegiance to Queen Elizabeth. Unfortunately, he did not have More’s constancy, and after traveling in Italy and Spain for a few years, left the Church and became an Anglican sometime while working as a secretary for Sir Thomas Egerton. Disappointing, but I won’t doubt his sincerity given his reputation among those who knew him. He would eventually join the Anglican priesthood, despite feeling himself unworthy, after years of urging from his friends and even from King James I. He did suffer about ten years of hardship, though, because of his relationship with Anne More, who he secretly married because he knew he wouldn’t receive her father’s permission, which in those days was career suicide. In any case, he in his own lifetime he earned a prominent reputation for his works on theology, canon law, and of course, poetry. To give an idea of the respect other poets have had for Donne, his contemporaries Ben Jonson, Thomas Carew, Richard Corbett wrote poems in his honour, as did Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Coleridge’s son, Hartley, later on - and that’s just from a quick search; doubtless more examples can be found.