Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus

When writing about Tales of Mystery and Imagination, I mentioned that Edgar Allan Poe is an unusual member of the literary canon because of the types of stories he wrote, mostly horror. When thinking of comparable works, two come to mind right away. One is Dracula, by Bram Stoker. However, though Stoker’s vampire might be the most famous icon in horror, his work seems most influential in pop culture, rather than literature. Also, the novel kinda sucks (er, no pun intended). It reaches a climax too early, and was written in the horrid epistolary format, a style that has long since gone out of style, and good riddance.

Dracula’s only competitor for greatest horror icon is Dr. Victor Frankenstein and his monster, which brings us to a second work comparable to Poe, Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus, by Mary Shelley. Again, it’s most influential in pop culture, so much so that just as it’s hard to think of Dracula without thinking of Bela Lugosi or Christopher Lee, it’s hard to think of Frankenstein without imagining Colin Clive or Peter Cushing, or the monster apart from Boris Karloff. In literature, it’s an early prototype of both horror and science fiction; not exactly the most respected genres, but nonetheless, certainly worth something. It’s also very much in the Romantic mode, which may be a strength or a weakness, depending on the reader’s taste for melodrama. Most importantly, though, unlike Dracula it’s a genuinely good novel.

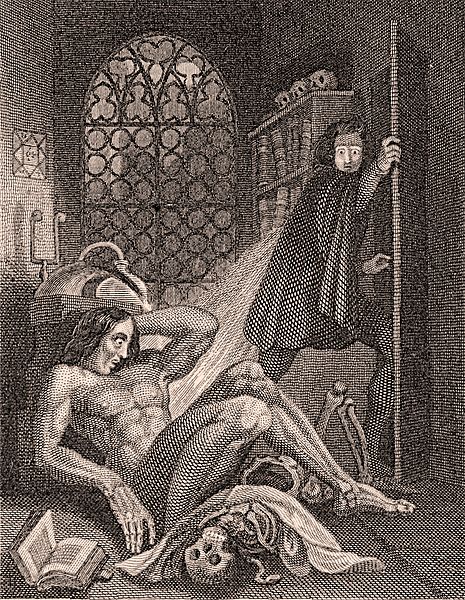

If you’ve seen any of the best-known film adaptations, you’ll know the premise already. Victor Frankenstein is a brilliant student of chemistry who, upon mastering this science, finds a way to bring life to the dead. Shelley keeps how he does this vague, but regardless, he eventually succeeds in creating a living man. As soon as he beholds his monster, though, he’s so sickened by what he’s done that he flees his laboratory and the monster escapes. Interestingly, Shelley tells Frankenstein’s story through a framing device. The novel is technically the letters of an arctic explorer, whose ship picks up Frankenstein as the scientist is pursuing his monster. After befriending him, Frankenstein tells him his story - which also means that we should take his narrative with a grain of salt, since besides the explorer’s brief encounter with the monster at the end, everything is from Frankenstein’s point of view. Not satisfied with a double narration, though, the monster eventually meets Frankenstein and tells his story since leaving the lab, giving us a rare and coveted instance of triple narration.

Anyway, something often pointed out about the novel that may come as a surprise to those who only know Karloff’s portrayal of the monster is how articulate he is. After getting used to his body and senses, he doesn’t shuffle around but is quite strong and agile, and he eventually makes his way to a small rural house. He lives in a small shed adjacent to it, and by observing the family living there learns to speak and even read. He also finds a package of three books left on a trail by some traveller, and so familiarises himself with Plutarch’s Lives, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Being a man of one, or rather three, books, and having plenty of time to reflect on his state, the monster is quite intelligent and thoughtful by the time he meets back with Frankenstein. When comparing Paradise Lost to his other books, he tells his creator:

But Paradise Lost excited different and far deeper emotions. I read it, as I had read the other volumes which had fallen into my hands, as a true history. It moved every feeling of wonder and awe that the picture of an omnipotent God warring with his creatures was capable of exciting. I often referred the several situations, as their similarity struck me, to my own. Like Adam, I was apparently united by no link to any other being in existence; but his state was far different from mine in every other respect. He had come forth from the hands of God a perfect creature, happy and prosperous, guarded by the especial care of his Creator; he was allowed to converse with and acquire knowledge from beings of a superior nature, but I was wretched, helpless, and alone. Many times I considered Satan as the fitter emblem of my condition, for often, like him, when I viewed the bliss of my protectors, the bitter gall of envy rose within me.

At this point, he says that he found he could read Frankenstein’s letters that had been left in the clothes the monster took before escaping the laboratory, which is how he learned who his maker was, where he came from, and was eventually able to make his way there. In the meantime, he had also become aware of his own terrible appearance, which made it impossible for him even to approach other people, and begins seeking revenge on Frankenstein. Indeed, by the time they met, he had already killed Frankenstein’s younger brother and framed a family friend for the murder. He promises to relent, though, if Frankenstein will create for him a mate like himself, much as God, seeing that it’s not good for Adam to be alone, created Eve so that they would have each other.

What makes Frankenstein more interesting than later horror tropes is that, though neither Frankenstein nor his monster are really “good guys,” both are in seemingly impossible situations. Frankenstein had pursued knowledge he shouldn’t have, but then abandoned his creation and tried to pretend that it never happened. When asked to create a wife for the creature, there’s no obvious way forward. The monster does have a good point, but then, there’s also no guarantee that this wife wouldn’t reject the first monster, or that a second person wouldn’t simply allow the monster to cause even more harm than he could alone. In fact, Frankenstein even considers the possibility that they may be able to reproduce, leading to a whole race of them. The monster, for his part, has killed innocents even before offering Frankenstein a chance to redeem himself, in a way, by making a companion for him. We can also, though, perfectly understand why the monster is so bitter about his treatment.

I’ll leave it there for now. I don’t think that Frankenstein is quite a great novel, but it is very good, and a perfect choice if you’re looking for something to read for Halloween that has a bit more substance than Poe’s stories.