Lewis Carroll, the Alice Novels, and Sensible Nonsense

‘As to poetry, you know,’ said Humpty Dumpty, stretching out one of his great hands, ‘I can repeat poetry as well as other folk, if it comes to that — ’

‘Oh, it needn’t come to that!’ Alice hastily said, hoping to keep him from beginning.

‘The piece I’m going to repeat,’ he went on without noticing her remark, ‘was written entirely for your amusement.’

Alice felt that in that case she really ought to listen to it, so she sat down, and said ‘Thank you’ rather sadly.

When it gets late in the year and with Christmas coming soon, I always find myself in a nostalgic, and somewhat lazy, mood. It’s a time when my reading goes back to old favourites, and these past couple weeks I’ve revisited a couple of my favourite novels from yesteryear, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass.

Now, I went through The Annotated Alice, which is my favourite edition of the novels, and in the introduction editor Martin Gardner makes what seems, at a glance, a startling claim: “The fact is that Carroll’s nonsense is not nearly as random and pointless as it seems to a modern American child who tries to read the Alice books. One says ’tries’ because the time is past when a child under fifteen, even in England, can read Alice with the same delight as gained from, say, The Wind in the Willows or The Wizard of Oz.[…] It is only because adults […] continue to relish the Alice books that they are assured of immortality.”

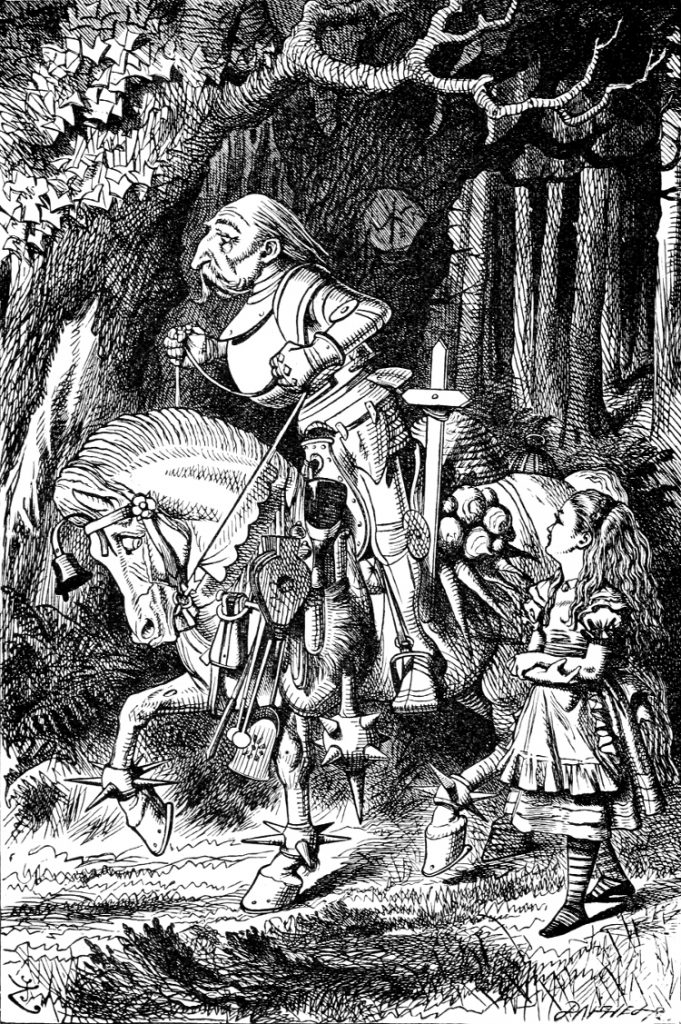

There are two claims here, so let’s start with the first: are the Alice novels really no longer children’s books? To be honest, I didn’t read them as a child, but first read them when I was about fifteen, coincidentally the age Gardner mentions above, though I do remember liking Disney’s adaptation of them. I can say that it’s not hard to find editions of the novel aimed at children, or at least older children, as well as at least one alphabet book. Gardner says that “Children today are bewildered and sometimes frightened by the nightmarish atmosphere of Alice’s dreams.” The books are surprisingly violent in parts and almost every character is a jerk to some degree, with the White Knight (very likely a stand-in for Carroll himself) and perhaps the Cheshire Cat as the only exceptions, but I’d hardly call either Wonderland or the Looking-Glass world “nightmarish,” and how frightened a child is would depend on the child. I’d have probably loved it.

It is true that children today won’t catch much of the referential humour, but recognising the source of Carroll’s various song parodies and such isn’t critical to enjoying the parody, and even if a reader misses one joke, there are so many throughout the books that it won’t be long until he comes to another one he may enjoy. Take, for example, the parody “You Are Old, Father William,” which Alice repeats for the Caterpillar:

‘You are old, Father William,’ the young man said, ‘And your hair has become very white; And yet you incessantly stand on your head– Do you think, at your age, it is right?’

‘In my youth,’ Father William replied to his son, ‘I feared it might injure the brain; But, now that I’m perfectly sure I have none, Why, I do it again and again.’

‘You are old,’ said the youth, ‘as I mentioned before, And have grown most uncommonly fat; Yet you turned a back-somersault in at the door– Pray, what is the reason of that?’

‘In my youth,’ said the sage, as he shook his grey locks, ‘I kept all my limbs very supple By the use of this ointment–one shilling the box– Allow me to sell you a couple?’

That’s the first half. Do you recognise the source? Probably not, but it doesn’t really matter. Carroll himself, as the narrator, even shows some awareness that he’s writing for a young audience. During the trial at the end of Wonderland, for example, we have this incident, with authorial commentary:

Here one of the guinea-pigs cheered, and was immediately suppressed by the officers of the court. (As that is rather a hard word, I will just explain to you how it was done. They had a large canvas bag, which tied up at the mouth with strings: into this they slipped the guinea-pig, head first, and then sat upon it.) ‘I’m glad I’ve seen that done,’ thought Alice. ‘I’ve so often read in the newspapers, at the end of trials, “There was some attempts at applause, which was immediately suppressed by the officers of the court,” and I never understood what it meant till now.’

Some young children probably would be disturbed at stuffing guinea pigs into a sack and sitting on them, even if done by other animals about the same size as a guinea pig, but this is certainly no grislier than many fairy tales, at least in their traditional forms.

So, it seems that Gardner overstates the case - but I do think he’s partly right. The second issue raised in the above quotation is: Are the Alice novels really books for adults? Why would an adult read these novels?

There are a few possible answers. One is nostalgia; the Alice novels, even if less accessible to children than they used to be, are still very much associated with childhood and remind adult readers of their own youth. A more cynical answer is that it’s a symptom of extended adolescence, much like adult colouring books or the obsession over Harry Potter or Star Wars. There probably is a grain of truth to this, as well, though an interest in (not, of course, an obsession over) Carroll’s work is more justifiable than Rowling’s. For one, Alice has embedded itself not only into popular culture, but is so often referenced in other works that it’s become one of the extremely few children’s books that could be considered part of the literary canon.

Besides that, Lewis Carroll isn’t just a writer of nonsense - he’s an exceptional writer of nonsense.

You see, the key to grasping all of Carroll’s work, not just the Alice novels, is to understand that “nonsense” does not simply mean “random.” Consider, for example, this famous exchange between Alice and the Cheshire Cat:

‘Cheshire Puss,’ she began, rather timidly, as she did not at all know whether it would like the name: however, it only grinned a little wider. ‘Come, it’s pleased so far,’ thought Alice, and she went on. ‘Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’

‘That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,’ said the Cat.

‘I don’t much care where–’ said Alice.

‘Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,’ said the Cat.

‘–so long as I get SOMEWHERE,’ Alice added as an explanation.

‘Oh, you’re sure to do that,’ said the Cat, ‘if you only walk long enough.’

Alice felt that this could not be denied, so she tried another question.

The Cheshire Cat is, as Alice notices, completely correct on all points.

This is why I recommend that adults read an annotated edition of the novels, like Gardner’s. Though they’re entertaining even on a surface level, there’s more going on than is immediately obvious. This first applies, of course, to the referential humour that can be hard to catch for modern audiences, as well as inside jokes intended for Carroll’s initial audience, the daughters of his friend Henry Liddell. During the caucus race chapter, for example, each of the various animals present represents someone they knew. For instance, Gardner explains, “The Lory, an Australian parrot, is Lorina, who was the eldest of the [Liddell] sisters (this explains why […] she says to Alice, ‘I’m older than you, and must know better’).”

This sensible nonsense is to be expected, really, since Carroll’s day job was a mathematician. What happens when a mathematician writes a children’s book? Well, when Alice gets to the bottom of the rabbit hole and tries to think back on her lessons, she says to herself, “I’ll try if I know all the things I used to know. Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is–oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate!”

Why won’t she get to twenty? Gardner explains:

The simplest explanation of why Alice will never get to 20 is this: the multiplication table traditionally stops with the twelves, so if you continue this nonsense progression - 4 times 5 is 12, 4 times 6 is 13, 4 times 7 is 14, and so on - you end with 4 times 12 (the highest you can go) is 19 - just one short of 20.

A. L. Taylor, in his book The White Knight, advances an interesting but more complicated theory. Four times 5 is actually 12 in a number system using a base of 18. Four times 6 is 13 in a system with a base of 21. If we continue this progression, always increasing by one until we reach 20, where for the first time the scheme breaks down. Four times 13 is not 20 (in a number system with a base of 42), but “1” Followed by whatever symbol is adopted for “10.”

He then gives a recommendation for further reading. That’s an extreme example, but far from an isolated one.

Now, this sort of thing has encouraged a great deal of over-analysis of the novels, which is why I highly recommend Gardner’s edition of them. Though some of his notes are a bit of a stretch, he stresses in the introduction that he tries to avoid both pedantry and overemphasising symbolic interpretation of the works. One example he points out for why symbolism shouldn’t be overstated is Tweedledee and Tweedledum’s famous poem, “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” from Through the Looking-Glass:

As a check against the tendency to find too much intended symbolism in the Alice books it is well to remember that, when Carroll gave the manuscript of this poem to [John] Tenniel for illustrating, he offered the artist a choice of drawing a carpenter, butterfly, or baronet. Each word fitted the rhyme scheme, and Carroll had no preference so far as the nonsense was concerned. Tenniel chose the carpenter.

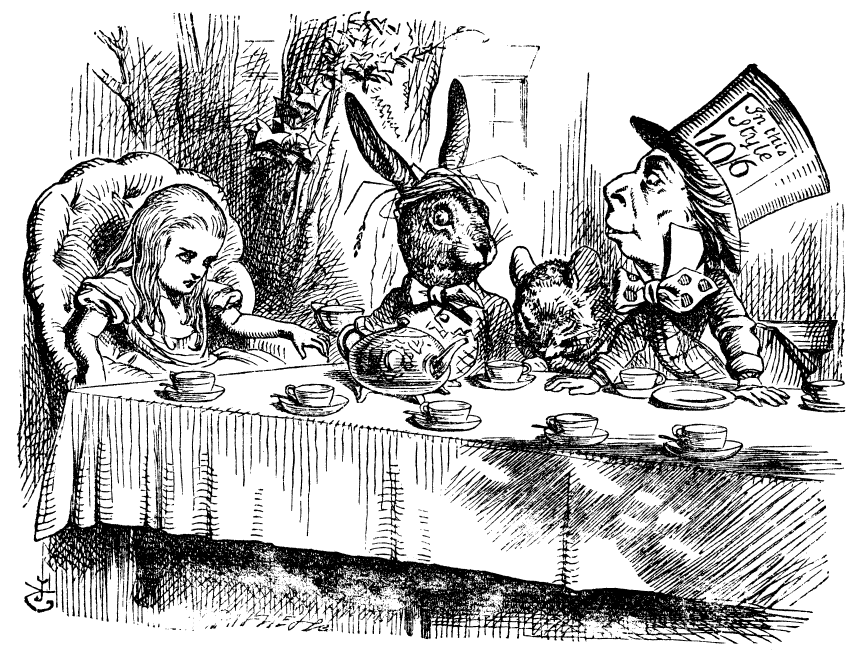

Speaking of Tenniel, the above is why it’s also best to pick an edition with his original illustrations. Though many artists have illustrated these novels, Tenniel’s work will always be preeminent because he worked directly with Carroll, so his will be closest to what Carroll intended for his work - not that he didn’t take some liberties. Carroll specified that the White Knight in the Looking-Glass world mustn’t have whiskers or look old, and, well:

In any case, I’ll add one more note on choosing which version of the books to get. Often, when looking for annotated editions of classic literature, one looks to Norton Critical Editions, and there is one available for these, edited by Donald J. Gray. It does have two advantages over Gardner’s version. First, it includes Carroll’s epic poem The Hunting of the Snark, and second, it includes a section at the back of background material, including excerpts from biographies of Carroll, his letters, and diaries. Having Snark is convenient and though the biographical details aren’t necessary to understanding the works, they are interesting for those who like to know a bit about the authors of what they read.

However, those are Norton’s only advantages. The book, though good quality for a paperback, is nowhere near as handsome a volume as Gardner’s edition. The notes, though useful, are much shorter than Gardner’s and sometimes just paraphrases of him. Some readers may prefer the more minimalistic notes, but Gardner is so obviously enthusiastic about his subject that he’s always interesting, even when going off on a tangent. Then there’s the Criticism section, which, well…

See, there are a few essays that are alright. Most, though, are just academic blathering. Not harmful necessarily, except insofar as wasted time is harmful. Then you get essays like Gilles Deleuze’s:

Alice has three parts, which are marked by changes of location. The first part (chapters 1-3), starting with Alice’s interminable fall, is completely immersed in the schizoid element of depth. Everything is food, excrement, simulacrum, partial internal object, and poisonous mixture. Alice herself is one of these objects when she is little; when large, she is identified with their receptacle. The oral, anal, and urethral character of this part has often been stressed.

… and so on. Do any of these essays help the reader understand the novels? No, but they do help the reader understand why it would be a good idea to drive a tank into Harvard Yard.

In any case, if you’re looking for some light reading or perhaps a gift for your favourite Carrollian, get a copy of The Annotated Alice. To adapt an observation of the White Knight, everyone who reads it enjoys it, or else - or else they don’t, you know.