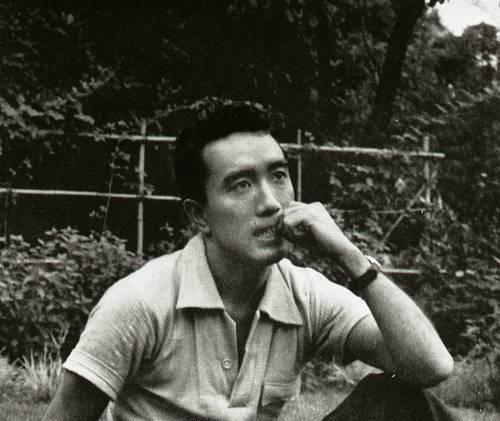

Mishima's 'Sun and Steel'

Mishima Yukio has quickly become one of my favourite authors. The hardest part of writing a post about him, though, is probably deciding just what to focus on, as he was tremendously prolific. In his 20-year career, he averaged at least one full novel a year, one full play a year, several short plays and short stories, as well as some essays and poems. I suppose the best place to start would be Sun and Steel, where he explains the philosophy and aesthetic that underlies his novels.

The central problem Mishima confronts is how to reconcile words, which I understand as analagous to mind or spirit, with the body, the physical world which does not depend on words and which words often cannot describe. The former he felt he mastered at a young age. After all, he made his living as a novelist, read widely, and was naturally introverted as a child.

The body he began to understand only gradually, through a handful of experiences. He relates how, as a child, he would watch religious processions of young men carrying mikoshi (portable shrines) through town, and noticed that they all looked up toward the sky as though experiencing an epiphany. He wondered what they saw and thought. Years later, he took part in such a procession, and as he felt the weight of the mikoshi on his shoulders and began marching in step with the other young men, he realised what they had all been thinking: nothing at all. They were merely gazing at the sun.

When I first read that story, it struck me as anticlimactic. However, I think it relates partly to an older Japanese tradition. Famed swordfighter Miyamoto Musashi noted (in his Book of the Five Rings) that a skilled warrior does not consciously plan his moves, but acts and reacts to an opponent by a kind of instinct. Miyamoto and Mishima refer to a kind of knowledge that does not rely on the intellect, and which words cannot quite adequately describe. While many philosophies (e.g., Confucianism) urge cultivation of the intellect, they often neglect this physical knowledge which, according to Mishima properly forms fully half of human experience.

So, to be a full man, one must cultivate both the body and the intellect. After a man’s gotten a library card and gym membership, though, what should he do next? Is there a way to reconcile these two types of knowledge? The question persists through several of his novels to varying extents. See, for example, Runaway Horses, the second book in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy. The story takes place in pre-World War II Japan, and the protaganist, Iinuma Isao, has mastered control of his body through kendo, and has also kept his spirit completely pure. This purity leads him to decide that he must, somehow, serve the emperor by protecting him from the corrupted politicians and capitalists who control Japan. His purity gives him the will and his body gives him the ability to act, and his solution is to gather like-minded comrades and then assassinate certain key figures, then commit suicide after accomplishing that mission. They hoped that their own dramatic action would inspire the rest of the nation to demand a restoration of imperial authority.

One could also relate this, of course, to Mishima’s own decision to commit suicide, and in spectacular fashion at that. Along with a few followers, he took over a military office, demanded the restoration of imperial power, and then committed suicide. His inspiration came from words, his action from the body.

(image taken from Wikimedia Commons)