Moby Dick: The Picture Book

‘Of course’, said Queequeg. ‘Man want to die, nothing can save him. Man want to live, only God can kill him - or whale or storm, maybe’.

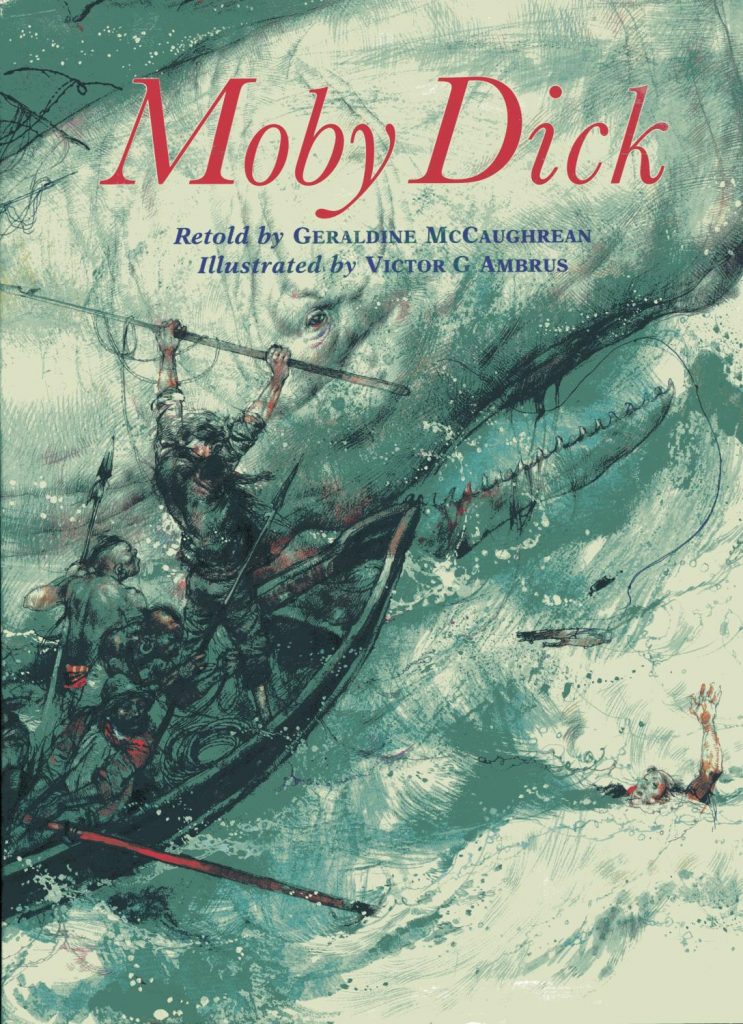

Recently, while shelving books in my library’s children’s section, I noticed a picture book with an especially striking cover and was somewhat surprised to see the title, Moby Dick. Herman Melville’s Great American Novel is hardly something I expected to find on the kid’s fiction shelves, but I was curious about how it would be adapted so I checked it out.

So, how did reteller Geraldine McCaughrean do it? One thing to note is that once you strip away Melville’s copious material about whales and whaling it’s not terribly difficult to then further abridge the story to a hundred-page adventure. It’s been a very long time since I’ve read the original, but by my memory the outline of all the major events are present and given in language that is appropriately simplified, but not dumbed-down. As a result, even some of the novel’s themes and philosophising survive. Take the first few paragraphs, for example:

There is a whale in the sea, as white as a ghost, and it haunts me. It haunts me on winter nights, when the sky tumbles like a grey sea, and drifts of snow hump their backs at me. It haunts me in summer, when the sun overhead turns the grass sea-green, and the almond blossom rears up white over my head.

Sometimes, when I’m afloat in sleep, like a drowned sailor, he swims towards me - a nightmare all in white, jaws gaping, and I wake up screaming and salt-water wet with sweat. Somewhere out there in the bottomless oceans lives Moby Dick, a great white winter of a whale, and I shiver at the thought of him. Even in summer.

Call me Ishmael. It might be my name. Then again it might not. In my devout, church-going part of the world, it is usual for parents to name their children after characters in the Bible. Maybe mine did. There again, a man can always choose a new name, later in life, to suit his nature and experience. I call myself Ishmael, like that despised son of Abraham cast out into the wilderness places of the world. He may have lived apart from other men, but God was with him in the wilderness, even so, and heard him when he cried. God hears. That’s the meaning of Ishmael. A man could be called worse. ‘Ahab’, for instance.

Three paragraphs, and clearly, though this looks like a picture book given its size and many illustrations, it’s not at all what one typically expects from children’s literature. I’m not sure how much of this is taken directly from Melville, but I don’t see any exact correlations from the novel, or even near correlation, at least from the beginning aside from the famous “Call me Ishmael.”

McCaughrean pulls no punches, either, as characters prepare for death and die, as Ahab’s obsession grows worse, as the ship meets its doom. We even get to see the word “damned” a couple times, which is always cool in a kids’ book. Notice how even in just the passage above she repeats motifs on the colour white, how the white humps of snow recall Moby Dick’s white hump, how the grass isn’t just green but specifically sea-green, and careful attention to the sound of words, like the rhyme of sea/me in the second sentence or the alliteration in, for instance, “screaming and salt-water wet with sweat” (with another rhyme in wet/sweat for good measure).

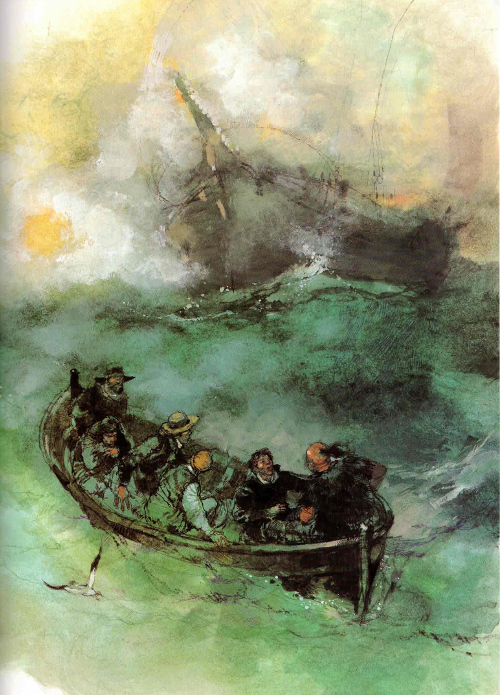

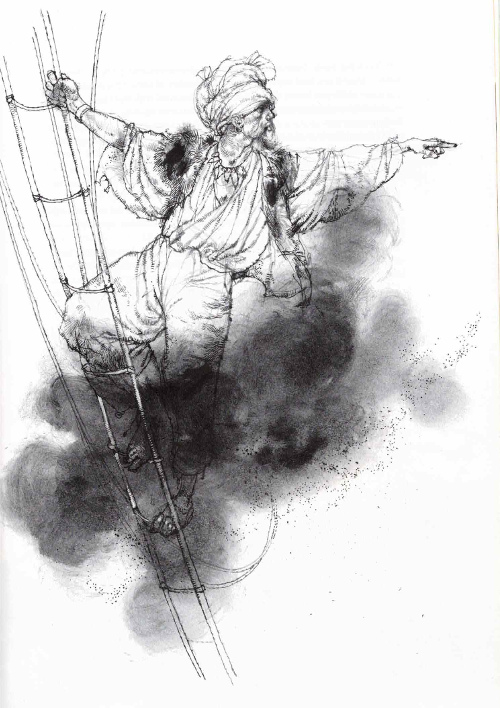

That said, if you want the full Moby Dick experience your best bet is of course still to read the original novel. The author does a stellar job presenting the story to an audience too young for the source material but still ready for serious literature, but the main appeal for adults are the wonderful illustrations by Victor G. Ambrus. Seeing Ambrus’s work in an edition of the full novel would be something I’d buy instantly.

Some will likely question whether we really need children’s adaptations of classic literature. In general, I think it is best simply to give children books appropriate for their age and let them grow into the classics. However, I do make some exception for mythology, and Moby Dick is very much part of American mythology. Enough so that I think that, given that most Americans will never read the original novel, it’s good to fill our children’s imaginations with some version of this tale.

Most books I see in the library’s children’s section are not childlike so much as childish. Having a much higher quality story available, then, is very much to be welcomed.