Seventeenth Friend: A. E. Housman, “Here Dead Lie We”

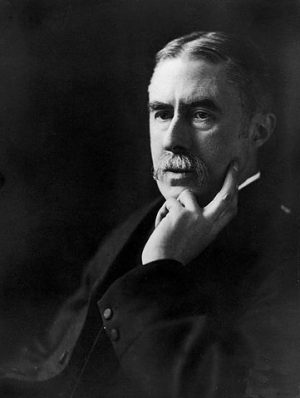

Today, we’ll meet Mr. Alfred Edward Housman, a popular English poet and a staple of English literature classes, so I assume that most folks are at least aware of him. He was born in 1859 and attended Oxford, but failed his final exam due to emotional turmoil, apparently due in part to struggling with homosexual desires. So, he spent ten years (1882-92) working as a clerk at the Patent Office while spending his free time studying and writing articles about Latin literature. Today that would’ve been the end of it since he didn’t have any official credentials, but those articles did gain scholarly attention and he was hired as a professor of Latin at University College, London, and later at Cambridge. His largest contribution to the Classics from there was in editing and annotating a still respected edition of Marcus Manilius’ Astronomica. He passed away in 1936.

Now, let’s set aside his academic career and look at his poetry. Most of his work is in a traditional English style, with regular metres and conservative rhyme schemes. They’re also on the pessimistic side, as in his most famous poems, “To an Athlete Dying Young” and “When I was One-and-Twenty.” One might worry that a Latinist writing in a conservative style would produce overly formal poems, but Mr. Housman is popular for good reason. His style is approachable even for general audiences and his themes are easy to relate to. For example, take a look at “To an Athlete Dying Young.”

The time you won your town the race

We chaired you through the market-place;

Man and boy stood cheering by,

And home we brought you shoulder-high.

Today, the road all runners come,

Shoulder-high we bring you home,

And set you at your threshold down,

Townsman of a stiller town.

Smart lad, to slip betimes away

From fields where glory does not stay,

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

Eyes the shady night has shut

Cannot see the record cut,

And silence sounds no worse than cheers

After earth has stopped the ears.

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

So set, before its echoes fade,

The fleet foot on the sill of shade,

And hold to the low lintel up

The still-defended challenge-cup.

And round that early-laurelled head

Will flock to gaze the strengthless dead,

And find unwithered on its curls

The garland briefer than a girl’s.

Anyone old enough to have been through high school will likely have known local athletes celebrated for their accomplishments, which are often soon forgotten, and those middle aged and older will have seen even famous professional athletes whom they admired when growing up now obscure and growing old. We can imagine how this may feel for the athlete itself, and it’s natural to wonder if, perhaps, it’s better in a way to die while still at the height of fame and renown.

Of course, when we’re young we assume, without much thought, that the good times will last forever. Early death is also the theme of this poem, “Here Dead Lie We,” which is a war poem:

Here dead lie we because we did not choose

To live and shame the land from which we sprung.

Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose;

But young men think it is, and we were young.

This is very short, but there a few things going on. Honour is important, and it’s extremely important to young men. The first two lines, then, might have us expecting either a patriotic work lauding them for their sacrifice, or to mourn their early deaths for something ambiguous like shame and honour, for what Wilfred Own called “that old lie,” “dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” (from Horace, “it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”).

The next two lines, though, are more ambiguous than that. “Life […] is nothing much to lose.” It’s not? Even if we consider it less important than shame and honour, the reason we praise men who risk their lives, even setting aside public holidays like Veterans Day, is because life is a great deal to lose. So, did the speakers not sacrifice much after all?

Maybe, but the last line takes a very subjective turn. “But young men think it is, and we were young.” The weight of sacrifice, apparently, is in the eye of the beholder.