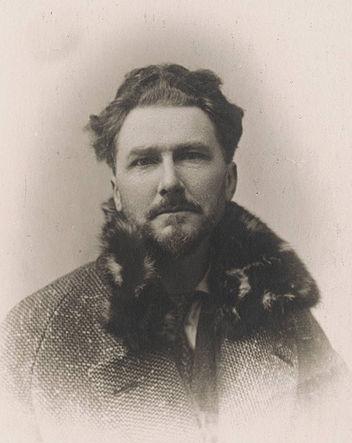

Fourteenth Friend: Ezra Pound, "A Pact"

I’ve written about today’s friend, Mr. Ezra Pound, a few times before, including addressing his war literature, a very short poem, and a brief reflection on his birthday. In literary terms, he’s a strong contender for the most accomplished friend we’ll meet during this whole series, as he was a great poet, a skilled though idiosyncratic translator, a thoughtful and opinionated critic, and an editor with a knack for finding and fostering talented writers. Because of all that he may be, apart from the Bard himself, the most important poet in English. His reputation suffered because of his support for Benito Mussolini, but I feel confident predicting that in a few centuries Mussolini will be a footnote to the Cantos, much as many great and powerful men are now footnotes to the Divine Comedy.