Chesterton and The Man Who Was Thursday

Note: This post was originally published at Thermidor on March 6, 2017, but since it recently shut down I’ve decided to republish my articles here. I plan to post one per week until they’re all back up, with only light editing.

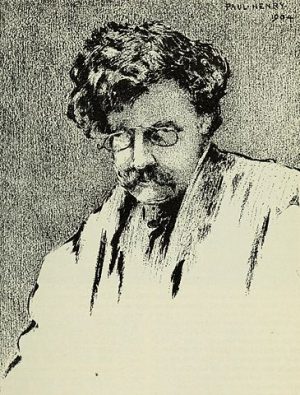

What’s there to say about G. K. Chesterton? He’s a contender for the most-quoted man on the Right; spend some time in any broadly Right-wing community, Conservative, Reactionary, or even just moderate Christian, and it won’t be long before someone quotes one of his famous aphorisms or anecdotes. Though not a particularly rigorous thinker, and a bit light for those used to reading the Joseph de Maistres and Julius Evolas of the world, he’s among the best authors who’ve written primarily for popular audiences.