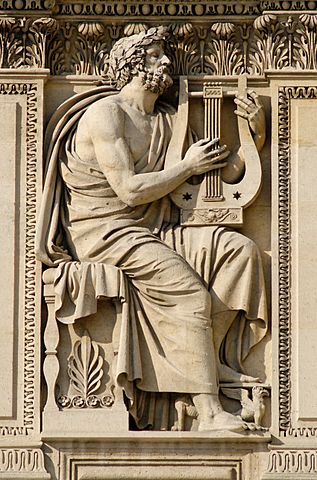

The Printed Homer: A 3000 Year Publishing and Translation History of the Iliad and the Odyssey

Philip H. Young’s The Printed Homer: A 3000 Year Publishing and Translation History of the Iliad and the Odyssey is an odd book to recommend to laymen because about half of it will be useful only to a very focused class of specialists. The other half, though, is of interest to any Classicist, professional or amateur, and is enough to justify buying the whole package.

The specialist half can be dealt with very briefly. Young has compiled a comprehensive list of every known printing of Homer’s works (including those spuriously attributed to him, such as the Hymns) from the first example in 1470 to 2000. It’s an impressive undertaking and I’m sure it’s very helpful for historians who specifically study historical interest in and treatment of the Homeric texts. For laymen such as myself, though, I find it hard to imagine a plausible scenario where this part of the book might be useful.