There are only two groups of Americans who are likely to know about the Hyakunin Isshu, literature enthusiasts who’ve taken an interest in Japan, and fans of the comic and anime Chihayafuru. I’m certainly the former and like the latter enough to have imported the French edition, so Frank Watson’s One Hundred Leaves: A New Annotated Translation of the Hyakunin Isshu seemed like a must-have to me.

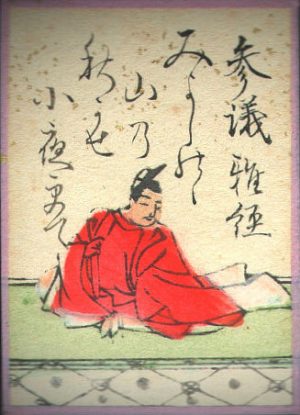

If you’re not in either of those groups, the Hyakunin Isshu is an anthology of one hundred poems, each by a different poet, compiled by poet and critic Fujiwara no Teika around 1237. For readers, myself included, who don’t have a lot of experience with Japanese poetry, Watson does offer a few things to help us out. There’s a short introduction on appreciating this style of poem, annotations explaining the intricate wordplay that characterises these works, and a “literal” translation of each poem to supplement the main translation. He also includes the original versions, both in Japanese script and English transliteration, for those who either know a little Japanese or want to read them out loud. Finally, he also provides a painting from traditional Japanese art to complement each poem. Unfortunately, a few aspects of the presentation do fall short of the ideal. The pictures are in black-and-white with no indication of the title or artist, and it’s sometimes hard to see what the picture has to do with the poem it ostensibly illustrates. Not all poems have annotations, either; some stand on their own well enough not to need much explanation, but it would be nice to at least get a short biographical note about the writers. The annotations also get a little repetitive; for example, he explains several times that the image of “wet sleeves” indicates wiping away tears. As for the translation itself, my Japanese is nowhere near strong enough to speak for the accuracy, but Watson does have some poetic sense, and when faced with multiple possible interpretations of a poem he typically uses the more literary, which I think is the best approach. Comparing them with Joshua Mostow’s translation, which you can find with annotations at this blog, he’s often a little more clear. Compare Watson’s translation of poem 31, by Sakenoue no Korenori: