Tales of Mystery and Imagination

It’s October and Halloween is just around the corner, so now’s a perfect time to bring out Tales of Mystery and Imagination. Not the Alan Parsons Project album, though that’s good, too, but Calla Editions’ reprint of the classic collection of Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories.

Now, among the authors typically assigned for high school English, Poe stands out a bit from other members of the literary canon because, though many other canonical authors wrote for popular audiences, Poe’s stories come across as essentially pulp. It revels in the macabre, often hinges on suspense, and he’s primarily known for horror, and that genre is known for getting snubbed by critics. Most of his stories, because they sometimes do rely on the unknown, don’t benefit from re-reading like most great works, and Poe himself was strongly opposed to didactic fiction, so there aren’t many lessons to take from him, besides things like “Don’t bury your sister unless you’re absolutely certain that she’s dead,” or “Never bet the devil your head.” So what’s he doing on lists of canonical authors?

Simply, because he’s the master of this type of fiction.

‘For the love of God, Montresor!’ ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘for the love of God!’

Poe’s philosophy for poetry, which he also applied to his fiction, is that a work ought to aim at conveying one primary emotion, hence his focus on lyric poetry and short stories, rather than novels. For him, of course, that emotion is horror, and though he does have twist endings, his is a slow-paced form of horror, mostly based on atmosphere. If one were to summarise, say, “The Masque of the Red Death” or “The Pit and the Pendulum,” the result wouldn’t sound too exciting. Rather, Poe shines in his descriptions of his characters’ neuroses, where they live, the furniture they own, what they read, and so on. For example, here’s a passage from “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” just after the narrator and a friend take up a new residence:

It was a freak of fancy in my friend (for what else shall I call it?) to be enamored of the Night for her own sake; and into this bizarrerie, as into all his others, I quietly fell; giving myself up to his wild whims with a perfect abandon. The sable divinity would not herself dwell with us always; but we could counterfeit her presence. At the first dawn of the morning we closed all the massy shutters of our old building; lighted a couple of tapers which, strongly perfumed, threw out only the ghastliest and feeblest of rays. By the aid of these we then busied our souls in dreams - reading, writing, or conversing, until warned by the clock of the advent of the true Darkness. Then we sallied forth into the streets, arm in arm, continuing the topics of the day, or roaming far and wide until a late hour, seeking, amid the wild lights and shadows of the populous city, that infinity of mental excitement which quiet observation can afford.

This paragraph is by no means necessary for the story, but is just the sort of description of character and setting Poe revels in, and it’s what makes stories like “The Cask of Amontillado” so popular, even though their plot could be explained in a few sentences.

Poe did write in a few genres besides horror; “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” and to a lesser extent “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” are primarily mysteries. “Some Passages in the Life of a Lion (Lionizing)” is, of all things, a comedy, though with a characteristically grotesque moment at the climax. All but a few entries in Tales of Mystery and Imagination, though, are horror, which is fine because that’s what he’s deservedly best-known for, and made up the larger part of his work.

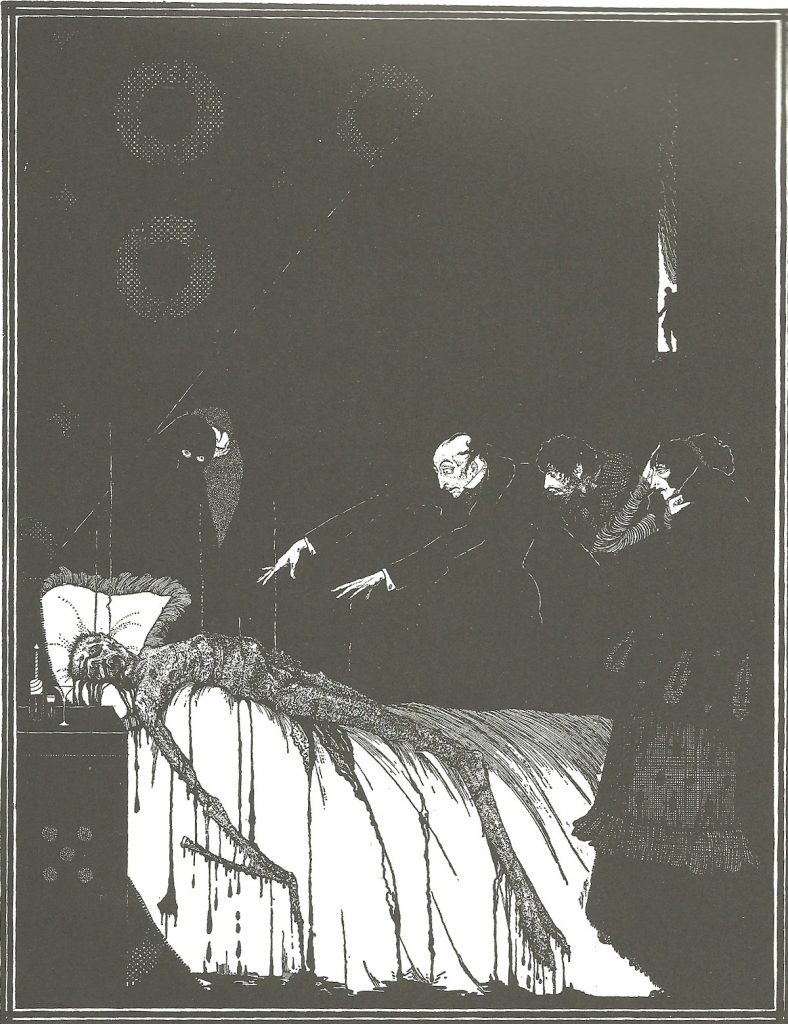

Upon the bed there lay a nearly liquid mass of loathsome - of detestable putridity

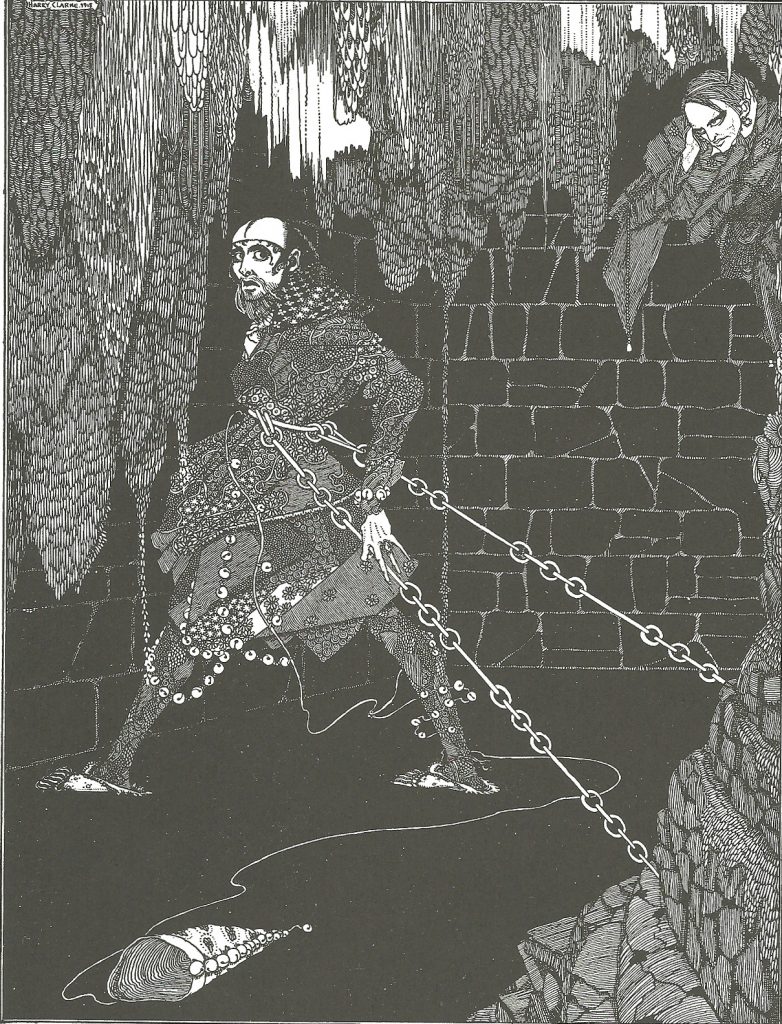

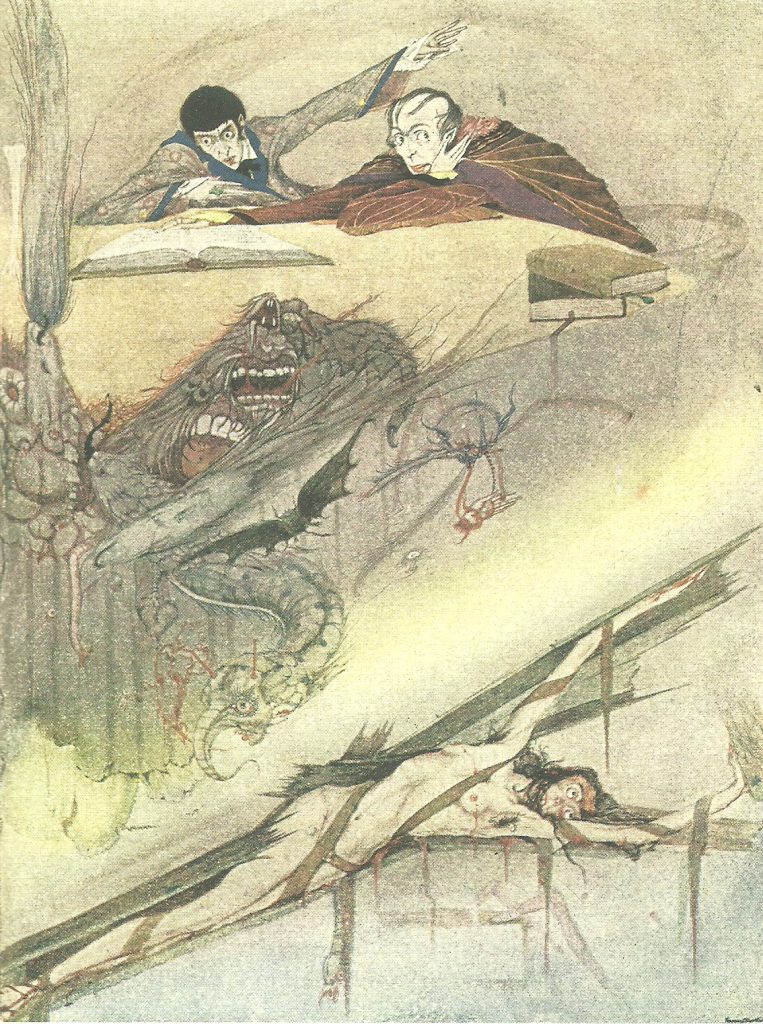

Again, I read Calla Editions’ version of the book, which includes Harry Clarke’s illustrations from the 1923 edition of Tales. It’s a large hardcover with nice paper quality, and Clarke’s illustrations are a perfect match for the stories. For fans of Poe, this is probably the edition to get, but there are a few caveats. As a nitpick, it could use a dust jacket, and I wouldn’t have minded a proper introduction or at least notes on where and when these stories were originally published.

More significantly, readers should note that Tales is not a complete collection. The poems are completely excluded, of course, but so are many stories. This has twenty-nine of them, while my copy of Dorset Press’s The Complete Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe has sixty-eight. Tales of Mystery and Imagination does have all of the essential ones, though, so while completists may want to look elsewhere for a chance to read “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Feather” or “The Balloon-Hoax,” Calla’s book is more than adequate to get a solid, working knowledge of Poe’s fiction. He was, after all, nothing if not consistent, so you really only need to read a couple of his stories to know if you’ll like him or not and whether you’ll enjoy a more complete compilation.

Say, rather, the rending of her coffin