The Pillow Book of Art Garfunkel

So, I suppose I’ll start with something of a confession: I love Boomer music.

Yeah, I know, as a Reactionary half their age, I’m supposed to despise Der Ewige Boomer, but I can’t help myself. Most of the music I listen to was recorded in the 1960s or ’70s, and though I try to make up for it by mixing in some music either much older than that or a bit newer, my favourites are what they are. I offer no excuses for my borderline-plebeian musical preferences.

That’s all just to explain why I’m interested in today’s subject in the first place. It came to my attention last year when a friend told me that Art Garfunkel would be at Southern Methodist University to talk about a new book of his, What is it All but Luminous, in the form of an interview with a columnist with the Dallas Morning News and a Q&A session afterwards (you can find an account of it here, if you’re interested). The interview had a few interesting points, while the questions from the audience varied wildly in quality, as one would expect. Each of the attendees also received a signed copy of the book, and though it’s not the most personally meaningful autograph I have (that would be ABe Yoshitoshi’s, for those wondering), it is the most famous by a wide margin. What is it All but Luminous is, I suppose, a memoir. Most of the work is composed of brief anecdotes, seldom more than a couple pages, from throughout Garfunkel’s life and career. So, take the first couple paragraphs, beginning in media res, as it were:

I was a nervous wreck as I packed my things in the middle of the night on January 2, 1969. There in my exposed-brick bachelor apartment on East Sixty-eighth Street, I was leaving the life of four years of a girl-chasing studio rat - a life of global good fortune - to cast my fate among actors. As a music star with no acting experience, I was acutely aware that I was cross-hopping professions. Yes the Panavision movie camera is like the Neumann microphone (little things are so magnified) but how would I be received in Mexico among first-rate actors on a social level - amongst Alan Arkin, Jon Voight, Orson Welles? I quivered with insecurity as I prepared to fly, the next day, into Mike Nichols’s third feature film, his follow-up to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and The Graduate - the World War II black comedy Catch-22.

*

Why did Mike cast me to play Captain Nately, the innocent? What about my famous singing partner? These are things I didn’t ask myself. Innately I felt the rightness of strengthening my half of Simon and Garfunkel. Paul was the writer. Paul played guitar. I was the singer, co-producer of the records, waiting for the songs to be written to start our fifth, our last album. In my mind, I played the underdog. I remember Paul being considered for a role in the movie. Or to rephrase - both of us were cast, Paul was dropped. Musicians don’t talk. We were too hip to share out loud hurt feelings inside. No one begrudged Ringo when he sang “They’re gonna put me in the movies.” It was held in affection. Mike knew it was my right to expect the same. Recall, he once also had a brilliant partner. In May of ‘69, Mike took the film to Rome, and Paul’s writing changed from “I know your part will go fine” - words of a deep friendship (“The Only Living Boy in New York”) - to “Why don’t you write me?” - words of frustration.

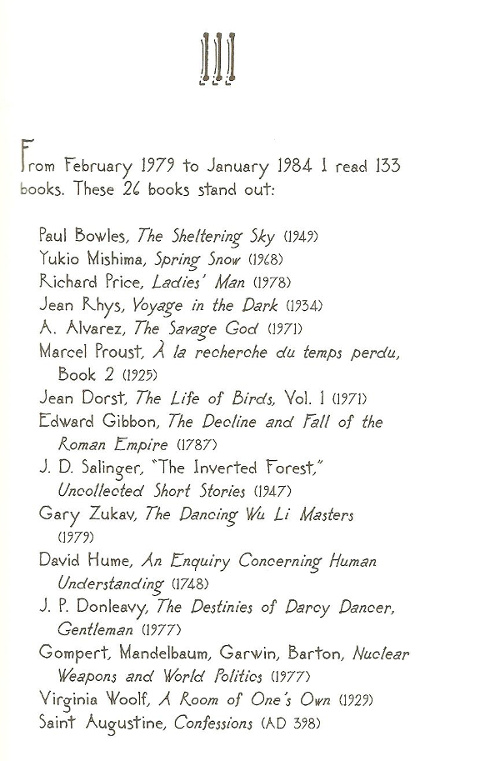

Each chapter is in roughly chronological order, but they’re not connected in any sort of a narrative as one would expect of a conventional autobiography. Even Bob Dylan’s Chronicles is more coherent. Also, among these anecdotes are poems, lists of books he read during a given period, and miscellaneous observations on this or that. While thinking about how one would classify such an odd assortment of material, it occurred to me that he had, essentially, written a pillow book.

What’s a pillow book? As far as I’m aware, it’s a form unique to Japan, and the most famous example is Sei Shounagon’s, a lady-in-waiting to the Empress in the Heian period, who wrote hers roughly around A.D. 1000. It’s a fascinating look into court life in that era, and as you may have guessed, it’s largely a diary filled with anecdotes of whatever had happened on a given day, but also poetry, lists, and whatever else she felt like writing. Take, for example, the famous first entry:

In spring it is the dawn that is most beautiful. As the light creeps over the hills, their outlines are dyed a faint red and wisps of purplish cloud trail over them.

In summer the nights. Not only when the moon shines, but on dark nights too, as the fireflies flit to and fro, and even when it rains, how beautiful it is!

In autumn the evenings, when the glittering sun sinks close to the edge of the hills and the crows fly back to their nests in threes and fours and twos; more charming still is the file of wild geese, like specks in the distant sky. […]

Now, I would love to say that an American had taken the title of Greatest Pillow Book Author, but Sei Shounagon’s position is quite secure. Though the anecdotes can be interesting, there’s not enough substance to them to be of interest to anyone who’s not a fan of Garfunkel’s. The lists don’t really add much, and the poems peak at mediocre, for instance, at the beginning of Chapter X:

Big free show at the Roman Colosseum, six hundred thousand Italians, a year and a week ago.

I walk the Sienna road today through middle Italy.

Little we know of the way of things, of the Buddha’s art - of what will connect and what will remain apart.

As someone who’s read Poetry, I’ve certainly seen worse. Far worse. I’ve also seen far better, though, and there’s little reason to spend a lot of time with run-of-the-mill poetry.

On a side note, I also don’t like the publisher’s font choice, which is something I usually don’t even think about. It’s apparently based on Garfunkel’s own handwriting, and I understand what they were going for, but it comes across as a mere novelty.

So, is Luminous worth reading? If you’re a big fan of Garfunkel’s or have an interest in literary novelties, sure. Otherwise, though, I can guarantee that your life is no less complete if you skip this one.