The Road Home

Shortly after I began studying Chinese, I thought it would be interesting to check out some Chinese films. I can’t really understand spoken Chinese well yet, so admittedly, any movie would be more for entertainment and a touch of cultural immersion more than a language learning tool. Nonetheless, I decided to give The Road Home a shot recently since it’s well-reviewed and looked like a film my wife might also enjoy, which is rather rare with movies I like.

The Road Home was directed by Zhang Yimou and released in China in 1999. The movie is a bit unusual in that there are essentially two narratives, one told within a framing device that opens and closes the film, the other within the central portion. I’ll be a bit free with spoilers here, because the movie’s strength is its aesthetic and themes, not the plot. At the start we meet our narrator, Luo Yusheng, who is returning from a big city to his home village upon the news of his father’s death. His father, Luo Changyu, had been the village schoolteacher for forty years and died during a snowstorm while out seeking funds to rebuild the school building. When he arrives, his uncle and the village mayor inform him that they would like to hire a car to bring his father’s body back for burial, but his mother, Zhao Di, wants his body carried back in a ceremony that hadn’t been performed since the Cultural Revolution a good twenty years before at that point. Unfortunately, though they wanted to honour Di’s wishes, they lacked the manpower to carry this out since all the young men had, like Yusheng, left for the cities over the years, so they hoped to find a compromise.

Now, this framing device is filmed in black-and-white, but here it changes to colour as Yusheng narrates the story of how his parents met and married in 1958. This part of the film is visually beautiful, but the plot here is relatively simple. Di and Changyu were eighteen and twenty years old when he came to the village to teach. Di fell in love at first sight, tries to catch his attention and succeeds after a couple attempts, and her feelings are quickly reciprocated. However, he is called away due to a political investigation; he is able to sneak back briefly, but ultimately returns after a couple years.

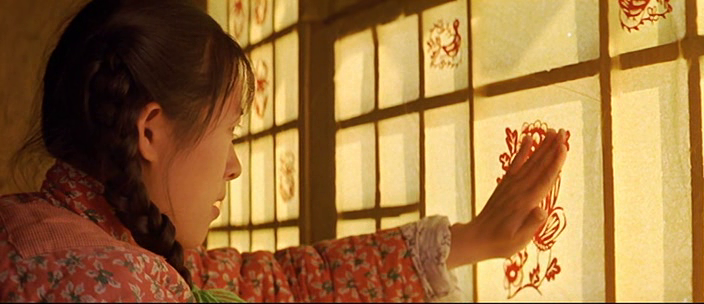

Decorating the school, awaiting Changyu’s return

We then return to the present day of 1998, and again to black-and-white. Yusheng is able to pay to hire men to carry Changyu’s body, but so many of his former students return and volunteer to help that it’s not necessary. After the funeral Yusheng asks his mother to come live with him in the city; she declines and urges him to marry. She also asks him to consider becoming a teacher as his father had hoped, or at least teach at the village school for one day, which he does.

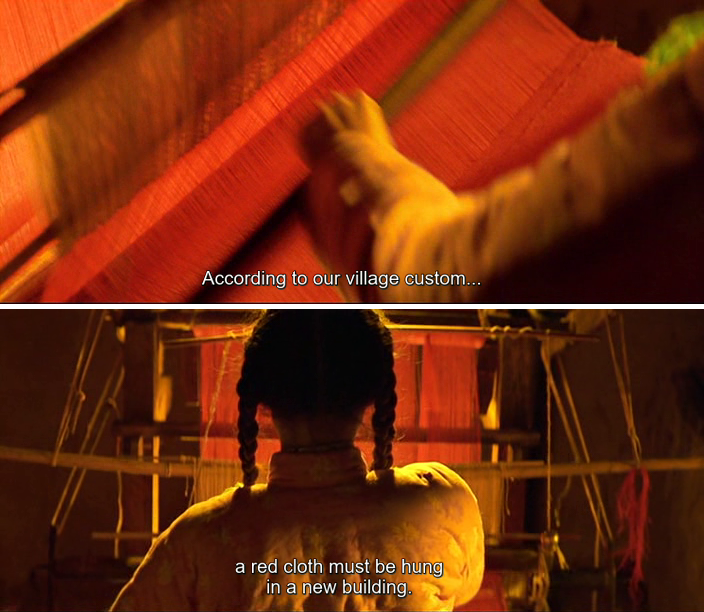

My wife enjoyed the love story and we both liked the look of the colour portion of the film. What stood out to me more, though, was the contrast between past and present. Zhang emphasises the contrast by using colour film and interesting camerawork for the 1958 segment, while the 1990s camerawork is much more conservative and in black-and-white. He also seems to call our attention to this in the pair of banners Zhao Di makes. When the school was opened in 1958 she made a red banner for it for good luck (quick note: red is a lucky colour in China; it doesn’t refer to Communist red here), and of course it’s a bright red on-screen. In 1998 she makes another banner to cover her husband’s casket, but of course with black-and-white film we can’t even tell what colour it is.

Weaving a cloth, 1958

Weaving a cloth, 1998

Of course, there’s the obvious difference in that the bright, colourful part of the film is about a marriage while the more solemn black-and-white part is about a funeral. It seemed to me, though, that something had been lost between 1958 and 1998. None of this is said explicitly, but the ceremony Di asks for has a sense of the transcendent, that is, it’s an extremely old custom that connects her generation back seemingly to eternity. Perhaps it gives her a sense that it will help her and Changyu connect to each other for eternity, as well. Yusheng, his uncle, and the mayor see the funeral as more of a practical matter. They want to give Di what she wants because of their appreciation for all Changyu had done for the village, but they’re concerned with the practical issues of how to pay for and organise the ceremony.

The old custom connects Di and Changyu’s old students to the past, but is there a connection from the present to the future? Yusheng isn’t married and apparently isn’t very young anymore (we aren’t told his exact age, but I’d guess thirties). Di urges Yusheng to marry soon, but he doesn’t want to talk about. Children, of course, are both literally and figuratively a family’s future, and it seems that Di is more concerned with not only the past but the future as well.

I’m unsure how much of this is intentional on the writers’ or director’s part. Certainly, the focus is telling a good story, as it should be, and I doubt my reading of the film would be viewed favourably by the CCP. In any case, it’s a fine movie whether you’re interested in this analysis or not, and an easy one to watch even with people who don’t generally care for foreign films.