The Spring and Autumn Annals and the Gongyang Commentary

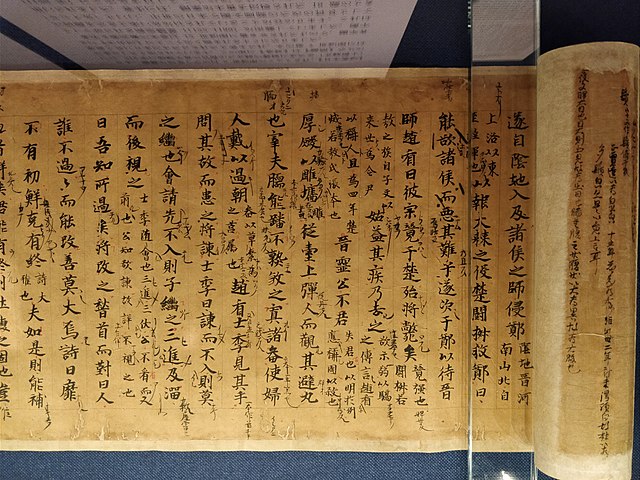

The Spring and Autumn Annals is one of Confucianism’s Five Classics, and like the Book of Documents is a work of history, in this case chronicling the history of the state of Lu, Confucius’ home state, from 722-481 B.C. However, whereas the Documents is, as the title indicates, a collection of speeches, decrees, and the like, the Annals is a chronology. It should take just one excerpt to give one an idea of the book, so from the very beginning, the first year of Duke Yin’s reign (722 B.C.):

It was the year one, in the spring, during the King’s first month.

During the third month, the Duke met up with Yifu of the state of Zhu Lou and made a pact with him at Mie.

In the summer, during the fifth month, the Earl of Zheng subdued Duan at Yan.

In the autumn, during the seventh month, the Heavenly King dispatched Zai Xuan to come bearing funerary offerings for Duke Hui’s wife, Zhongzi.

During the ninth month, a pact was made with men from the state of Song at Su.

In the winter, during the twelfth month, the Earl of Zhai arrived. Prince Yishi died.

Now, right away we can see a bit of a problem, and that’s a total lack of context for the events recorded. Even the Chinese themselves, much closer to the events described than we are, found the Annals rather obscure, and so scholars began writing commentaries on them, the three most important being the Zuo, Guliang, and Gongyang, which is the one I’ve just finished reading. The Gongyang Commentary is essentially a written version of a tradition of interpretation that started with Gongyang Gao, apparently a student of a student of Confucius. It was written down by his descendant Gongyang Shou and a man named Humu Sheng in the early Han dynasty (206 B.C. - A.D. 220). The book itself is in a question-and-answer format, similar to a catechism; since it was written for a similar purpose as a catechism, this isn’t totally surprising, as the format seems to be a popular one for doctrinal instruction. Again, one excerpt gives an idea of the flavour of the whole thing. Here’s part of the first section again:

In was the year one, in the spring, during the King’s first month.

What is meant by “the year one?” It means the year the ruler began his reign_. _What is meant by “the spring?” It means the beginning of the year. “The King” signifies whom? It signifies King Wen of Zhou. Why does the word “King’s” appear before the phrase “first month?” To show that it was the King who established the first month in the calendar. Why stress that the King established the first month of the calendar? To magnify the notion of the Zhou king’s unifying centrality. As for the Duke, why does the record say nothing about his succeeding to the ducal throne? Duke Yin wanted to set the state of Lu to rights and then to yield in favor of Duke Huan. Why would Duke Yin yield in favor of Duke Huan? _Because Duke Huan, though young, was noble, and Duke Yin, though senior, was lowborn. Their difference in birth was not obvious and was unknown to the people of Lu. Owing to Duke Yin’s seniority and to his worthiness, the various grand officers supported him and made him duke. If Duke Yin had simply refused the dukedom outright, he could never have been certain that it would pass to Duke Huan; and even if it did, he was afraid that the various grand officers would refuse to serve such a young ruler. Therefore, Duke Yin’s becoming duke was only for the sake of Huan’s becoming duke. _Since Yin was senior and, moreover, worthy, why should he not have been duke? _Because, while the sons of the legal wife are ranked by seniority and not worthiness, sons of concubines are ranked by nobility and not seniority. _So why was Huan considered noble? Because his mother was noble. Why is the son considered noble if the mother is noble? The son is noble because the mother is noble; the mother is noble if the son is noble.

Much better, and for those wondering, most comments are shorter than that. Many entries don’t have any comments, some have only a few sentences, and some have a few paragraphs.

In any case, it may still not be clear why the Confucians considered this work to be an important part of their canon. The Four Books (the Analects, Mencius, Doctrine of the Mean, and Great Learning) are all explicit in their philosophy and moral instruction. The Documents is less explicit, but it does contain a lot of advice on virtuous conduct from wise ministers and sovereigns, as well as anecdotes of moral exemplars good and bad. The Book of Odes is a bit more obscure on this front, but one can certainly read philosophical points out of them. The Book of Changes is also important to a society that took divination seriously, and the commentaries do have some serious points to make, while the Book of Rites has a clear significance to a philosophy that took the rites extremely seriously.

The Annals, I think, serves two purposes. First, the Confucians looked to history as a primary source for their ideas, and the Annals’ chronology provides a good deal of raw material for them. Secondly, though the annalists don’t editorialise, they do seem to express approval or disapproval of certain actions in rather subtle ways. For example, in the fourteenth year of Duke Huan’s reign (698 B.C.), the Annals records a conflagration at the ducal granary. In the next entry, it says “On the yi hai day, the First Taste sacrifice was held.” The Commentary’s student asks why such a regular event is recorded, and the teacher answers that it is recorded as a ridicule. The Commentary explains, “What’s being ridiculed is that the First Taste sacrifice was held at all, under the circumstances. The line of reasoning is, ‘Would anyone really go ahead with the First Taste sacrifice? The ducal granary was just burned! Why not simply call off the First Taste sacrifice just this once?’”

Yes, that’s right, even the Confucians are sometimes okay with not observing a specific rite.

I should also point out before proceeding much farther that one more reason for the Annals’ prestige is that Confucius is traditionally credited as its principal editor and compiler. That’s also true for much of the rest of the Five Classics, though also as with those books, the attribution is, apparently, dubious. Still, the Gongyang commentators do assume this to be the case and a few of their points rest on that assumption.

In any case, though the primary purpose of the Gongyang Commentary is to provide context and explanation of the events recorded, it also spends a good deal of time on interpretation. As one would expect of the Confucians, they’re principally concerned with observing the rites and practicing virtue, with a special emphasis on filial piety. Interestingly, they see filial piety as analogous to loyalty to one’s sovereign, and we see that in a striking passage from the eleventh year of Duke Yin’s reign (712 B.C.), when the duke is assassinated. The Commentary notes that no interment is recorded because the subject is taboo. It goes on:

In The Spring and Autumn Annals, when a ruler is assassinated, and his killer is not punished, his interment is unrecorded, for it is treated as though he had no subject ministers. According to Master Shen [a forerunner in the same tradition as Gongyang Gao], “If a ruler is assassinated, and his ministers fail to punish the murderer, then they are not ministers, just as a son failing to avenge is father is no son. Ceremonial interments are the responsibility of the living. In The Spring and Autumn Annals, if the sovereign lord is assassinated and the killer goes unpunished, then no interment is recorded, because it is as though the deceased left behind no minister to hold the ceremony on his behalf.

I should mention here that, though the Gongyang Commentary is certainly helpful, some of the comments read a lot into minor details, like minor differences in whether a person is referred to by his name or title. It’s not clear to me just how legitimate some of these are; it is conceivable that the chroniclers did express approval or disapproval of certain actions in such a subtle way, but in several cases it seems more likely that these really are just what they appear to be, minor stylistic choices.

Now, I read Harry Miller’s translation, which as far as I know is the only one in English. Miller does offer some helpful footnotes, typically a few of them per page explaining who certain people are, where this or that city is located, clarifying the commentators’ sometimes unclear logic, pointing to other works with more information, and so on. I do wish, though, that he had a more detailed introduction. All he gives us is a few pages, and I had to look around online even for information like when the work was probably written or who, exactly, Gongyang was.

One other odd thing about Miller’s introduction was his saying that he first took an interest in the work because another scholar, Joseph Levenson, mentioned it as something of a prototype of Chinese liberalism. I hope he didn’t expect to find a proto-liberal in an ancient Confucian, but fortunately, as far as I can tell he didn’t try to force such an idea into the book. As for the actual translation, I can’t judge its accuracy, but it is perfectly readable, or at least as readable as the Annals can be to a modern, Western audience, and he does explain a few translation choices in the footnotes that he thought may be controversial.

One final consideration is that this book is expensive. As of this writing, it’s about $90 on Amazon, and given its relative obscurity, I don’t expect to see many used copies floating around in the near future. Unfortunately, if you’re looking for the Annals this is still your least expensive option. As far as I’m aware, there is no English version of the Guliang Commentary, while the only edition of the Zuo Commentary will run you nearly $300 if you buy its three volumes as a set. James Legge did translate the Zuo Commentary, but I don’t know of a full in-print edition. Wikisource has his introduction, while Delphi Classics’ ebook of the Confucian canon has only his version of the Annals, without the Commentary or Legge’s introduction or notes. Is it worth that much? Honestly, only if you have a special interest in Confucianism, which will necessarily be incomplete if you’re not familiar with its canon. I am glad I read it, but much of the book is tough going, and its most important points are expressed more accessibly elsewhere.

I’m going to close this review with one more long quotation of perhaps the most memorable passage, at the very end of the book. The Annals often records marvels, natural disasters, and the like. Eclipses, for example, or floods, droughts, or the appearance of large numbers of elk. In the fourteenth year of Duke Ai’s reign (481 B.C.), we have just one entry:

It was the year fourteen, in the spring. During a hunt to the west, a unicorn was captured [Miller notes: “The Chinese word signifies a female unicorn, a deerlike animal with scales”]. Why is this recorded? To make note of a marvel. […] Why is it a great thing to capture a unicorn? The unicorn symbolizes humaneness. It appears when there is a true king and does not appear when there is no true king. As someone reported on this occasion, “It’s like a roe but with a horn,” to which Confucius said, “So! He is coming, then. He is coming!” He turned out his sleeves to wipe away his tears, until the front of his robe was dampened. When Yan Yuan died, Confucius said, “Alas! Heaven is destroying me!” When Sir Lu died, Confucius said, “Alas! Heaven is casting me off!” But when, “during a hunt to the west, a unicorn was captured,” Confucius said, “Now my Way has served its purpose.” Why does The Spring and Autumn Annals begin with the time of Yin? Because Confucius was able to learn of that time through the transmitted lore of his ancestors. Why does it end in the fourteenth year of Ai? The reason is that Confucius’s task was now completed_. _Why did Confucius write The Spring and Autumn Annals? For bringing order to chaotic times, for making things right again, nothing can approach the efficacy of The Spring and Autumn Annals. But how do we know if Confucius really wrote it for that purpose or if he simply delighted in expounding on the way of [ancient sage emperors] Yao and Shun? _In fact, anyone who delights in the way of Yao and Shun will thus know the mind of Confucius. The purpose of his compiling _The Spring and Autumn Annals was to keep it in readiness for a latter-day sage. No doubt Confucius took great delight in this task.