Welcome to the NHK (Novel)

In his mostly autobiographical comic Disappearance Diary, Azuma Hideo notes that in order to maintain an optimistic outlook on life, he’d removed as much realism as possible from his book. Azuma’s dry humour and cartoony art style make what should be a depressing story about a man running away from his responsibilities and living homeless seem rather light-hearted and funny.

Author Takimoto Tatsuhiko, in the afterword to his novel Welcome to the NHK, notes that his book also has a fair amount of autobiography. NHK also has a depressing subject, a twenty-two year old college drop out living as a shut-in (Japanese: hikikimori). Like Disappearance Diary, there’s a dry sense of humour, but here it serves to sharpen, rather than dull, the story’s edge, and though well-written, that edge makes it a sometimes difficult book to read. Our protagonist, Satou, meets a young woman named Misaki who decides to cure him, and he also spends a lot of time with his extremely nerdy neighbour and former high-school underclassman, Yamazaki. Takimoto pulls no punches in describing Satou’s life, from his social awkwardness, to his compulsive lying, to his drug trips, to his thankfully brief obsession with, um, pictures of little girls (if you’re thinking of Chris Hansen’s old show, yes, they’re those kinds of photos).

Now, some novels are uncomfortable to read because they’re poorly written, but NHK is one of those books that’s uncomfortable partly because it’s well-written; if you’ve read Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, you should have an idea what I’m talking about. The book’s highly subjective, almost stream-of-consciousness, first-person narration intensifies Satou’s faults. While writing for the erotic game he agrees to help Yamazki with, for example, he realises that the only experience he could use for ideas went back to his high school years, to an experience with a slightly older girl in a club he belonged to. However, “Doing so, I soon realized that those memories would move in an emotionally difficult direction. I hurriedly opened my eyes and tried to stop thinking about it.” He can’t help thinking about her now, though, and after a explaining a bit about their relationship he says,

A few days before graduation, she even let me do her once[…]

I felt like I should have done it a few more times. But then, I also felt that it might have been better for me not to have done it even that one time. I wondered which would have been right.

Of course, he doesn’t think for very long and thus, as he does a few times over the course of the story, voluntarily short-circuits what could be a painful but ultimately helpful process.

Takimoto presents Satou in a way that, though I would hardly call him a sympathetic character, we can understand somewhat why he acts the way he does. In the first chapter, Satou recounts the day he felt compelled to become a shut-in as he was walking to school.

However, my journey that day was decidedly different than it had been every other day. Everyone I passed looked at me. And I was absolutely positive that though it was very, very quiet - almost so quiet as to escape my hearing - each one of them let out something akin to a giggle. Of this, I was certain[…]

They each saw me and then began to ridicule me! The housewives and then the students, they all noticed me and laughed.

His self-consciousness is something I think many people can relate to, and the other character’s problems are handled similarly.

Also, as I mentioned, Takimoto does have a sense of humour. Satou is very self-aware, and his observations are often darkly funny. For example, at one point he and Yamazaki take a cocktail of over-the-counter drugs, and having previously decided to live a life of “sex, drugs, and violence,” go to the local park to fight.

Our fight was distressingly pastoral. There were some things that hurt, but punches from a weak man hopped up on drugs had limited force.

Satou isn’t the only character with serious problems, though. Every person he comes across is almost broken. Yamazaki is obsessed with porn games and wants desperately to live his own life apart from his domineering family, Misaki has no sense of self-worth, an old high school friend is unhappy about her upcoming marriage, and so on. The bulk of the novel is relentless about this theme of “quiet desperation.” Luckily, it does let up towards the end. A happy ending wouldn’t suit the story, and Takimoto doesn’t give us that. However, most of the characters do end up with lives that, even if not fully happy, are at least bearable.

This book did get an anime adaptation a few years ago, and that version adds several episodes not in the original. Mostly, these serve to flesh out Satou’s backstory and side-characters, especially the high school upperclassman, who doesn’t actually do much in the novel but is central to one of the major anime-only story arcs. Generally, I think the novel is slightly better because of the first-person narration, and the tighter construction doesn’t hurt. The anime’s additions are hit-and-miss as far as how much they add to the story. It’s better for including that upperclassman, for example, but worse for a few smaller additions, like Yamazaki and Satou’s trip to Akihabara, which is mostly just extra awkwardness.

There’s also a comic adaptation, but I’ve only read the first three volumes of that. Those volumes are okay, but nothing special.

There’s also a comic adaptation, but I’ve only read the first three volumes of that. Those volumes are okay, but nothing special.

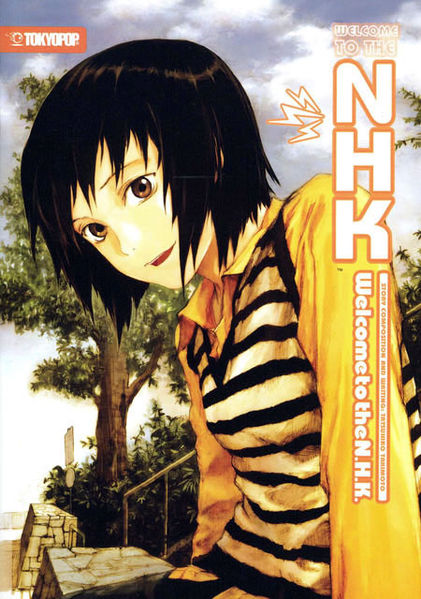

A few more notes: The cover art was drawn by Yoshitoshi ABe, character designer best known for his work on serial experiments lain and Haibane Renmei. It’s really nice, but unfortunately the cover is the only illustration he did for the book. The American edition was published by Tokyopop, and it’s pretty good quality for a paperback. The translation sounds good throughout, though it has more endnotes that it probably needs.

Unfortunately, NHK is long out-of-print, so even used copies go for around $50. Is it worth that much? It’s certainly worth reading, especially if you’re a fan of the anime, and is unique enough to be worth more than the most hardbacks, let alone a used paperback. If you’re on a tight budget, though, there may be better ways to spend $50 on literature, so I’d only recommend buying it if you’re already a fan, or if you don’t mind rolling the dice on a relatively expensive but potentially rewarding novel.