You're the Mandarin Now, Dog

Back in February, my mother-in-law came to visit my wife and I at our new home, and over dinner she told me that she was counting on me to teach our daughter Chinese. My wife insisted that she was joking, and I am sure that she’s right, but I wouldn’t let that stop me - I decided that I was going to learn Chinese.

Now, my interest in China and the Chinese language has, until relatively recently, been limited to the Confucian canon and the historical context needed to understand it. Naturally, though, I became curious about how Confucianism has been practiced in the real world, leading me to begin reading more history. The language, though, hadn’t ever piqued my interest beyond my general interest in any language. So, I began my study thinking I’d simply dabble in it for a few weeks, then set it aside and go back to my attempts at Latin. Instead, the opposite happened - Latin is on indefinite hold because studying Chinese has been the most fun I’ve ever had learning a language, by far.

Why this is, I’m not quite sure, but there are a few things that set it apart for me. One is the novelty; as one would expect, it’s very different from English in most respects. However, it’s different in ways that generally make it surprisingly easy. Not that it’s easy to become proficient, of course, but it’s not even close to its reputation as an exceptionally difficult language. For example, there is no conjugation or declension - a great relief coming from Latin! Not even pluralisation, with a few exceptions like pronouns. One figures out the tense or number from context. In the real world this degree of dependence on context may make things a bit difficult for me, since even in English I like having things spelled out explicitly, but so it goes.

Why this is, I’m not quite sure, but there are a few things that set it apart for me. One is the novelty; as one would expect, it’s very different from English in most respects. However, it’s different in ways that generally make it surprisingly easy. Not that it’s easy to become proficient, of course, but it’s not even close to its reputation as an exceptionally difficult language. For example, there is no conjugation or declension - a great relief coming from Latin! Not even pluralisation, with a few exceptions like pronouns. One figures out the tense or number from context. In the real world this degree of dependence on context may make things a bit difficult for me, since even in English I like having things spelled out explicitly, but so it goes.

I also like the aesthetic of the language. I love the ideograms, and am familiar with a few hundred of them through studying Japanese, which are the same or similar to their forms in China, though more so with traditional than simplified characters. Yes, these can be taxing on one’s memory, but one gets used to them through frequent use. The sound of the language seems more controversial; my wife, ironically, hates the sound of Mandarin despite having been born in and living in China for the first seven years of her life. I’ve heard it compared to the sound of silverware falling on linoleum.

Now that I’ve learned how to pronounce it and can recognise the sounds, it still sounds like silverware falling on linoleum, but I can make sense of the tumbling forks and knives and even appreciate the “sing-song” nature of the spoken language. Not that it’s apt to replace French as the language of love, and my wife’s favourite foreign language.

Beyond that, I suppose my interest is further strengthened by following more Chinese speakers on social media. Much like how my interest in Japanese was fueled by anitwitter and earlier anime communities, my interest in Chinese is fueled by the people I know who enjoy the country’s history, language, and culture, and enjoy talking about it.

I’ve been asked on Twitter a few times how I go about studying Chinese, and some specifics about what I study.

First, of the dialects, I study Mandarin. There are many others and I did briefly look into Cantonese, but Mandarin is the biggest and most common, and is what my mother-in-law speaks.

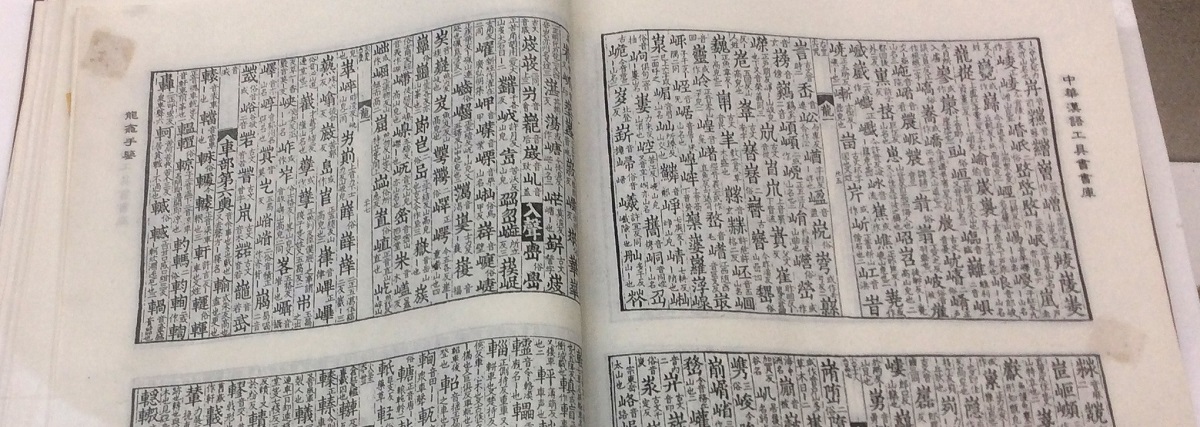

For the characters, my focus is on traditional, though I am picking up simplified along the way since it’s the default in the app I’m using and my dictionary’s flash cards display both character types side-by-side. I like the aesthetic of the characters more, and generally favour the traditional over the novel. They’re also easier for me, as the components are easier to make out and they’re usually, though not always, the same as or closer to the Japanese forms that I already know. They are also the norm in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and some other places.

That said, simplified characters have been around for decades at this point and are firmly cemented in mainland China. They also aren’t too bad as far as the aesthetic goes. Which type you should learn really just comes down to your own goals and preferences.

My primary tool for learning Mandarin has been the iOS app ChineseSkill, which is also available for Android. Their main course has, I think, given me a firm foundation to build on and start using the language confidently. They also have a lot of games and interactive dialogues, which make for decent practice. The main course supports traditional characters, but the games only use simplified for some reason. You do have to pay for all features, but it’s worth it and still far cheaper than taking a class.

Regarding books, Japanese students are likely familar with James Heisig’s excellent Remembering the Kanji. There are two counterparts for Chinese, Remembering the Hanzi, one for simplified characters and one for traditional. It’s the same Heisig method, though by a different author, of assigning a mnemonic keyword to characters and character components and developing stories using those keywords. It works as well with the hanzi as with the kanji, but of course you don’t learn the character readings.

So, I actually found myself using Gilbert-C. Rémillard’s Chinese Blockbuster. He essentially uses the Heisig method, but teaches both traditional and simplified characters side-by-side, and also includes mnemonics for the readings. The problem is that the reading mnemonics are inconnsistent and often difficult to remember, so while I found the first volume helpful overall, I’m going to see how well I can expand my vocabulary and character knowledge on my own before buying the seconf volume.

I’ve also tried Paul Noble’s Mandarin audio course which is generally good, at least at helping perfect my pronunciation.

Pleco is the dictionary everyone recommends, and so do I. Even some of the additional dictionaries, flash cards, and other features are worth paying for. I’ve found that I use the OCR function, for example, far more often than I expected, and I prefer Pleco’s flashcard system over the ubiquitous Anki. The only caveat is that whereas Anki is more-or-less “plug-and-play” with setting up your cards and studying, Pleco requires more finagling with menus to get things arranged how you want. For me, though, it’s been worth the effort.

Finally, I’ve ventured onto Weibo, China’s biggest and most famous social media site. I only post sporadically, more for my own practice than with the expectation that anyone would read it or follow me. For now, anyway. Most posts are well above my level, but I can tell that I’m understanding more as time goes on.