The First World War in Colour

Dan Carlin, in an episode of his Hardcore History podcast, called history from Herodotus onward the “colour era” of history, compared to the “black and white” era before Herodotus. The difference comes down to one of style - ancient histories were often little more than chronologies, with some propagandizing, but had relatively little characterisation or storytelling. From Herodotus onward, though, historians began treating their subjects in a more narrative style, which makes their subjects feel more “alive” to the audience.

Some historians are very good at this. Last year, for example, I gave Dan Jones’s The Plantagenets credit for his novelistic writing style, even if it was a bit overdone at times. In my reading, most popular historians do at least make an attempt to avoid getting bogged down in plain facts, figures, and abstractions, to give readers an idea of what the events they describe were like for the people who actually experienced them.

Nonetheless, history often is difficult to imagine for those of us who had no part in the events, especially for the distant past. I think I’m safe in speculating that there’s more interest in relatively recent events like the Second World War than earlier eras because, besides being more obviously relevant, there’s a lot more supplementary material. I can see many photographs and even film of the Second World War, and even listen to speeches by, say, Franklin Roosevelt or Sir Winston Churchill. This is even more true for still more recent history.

So, I’ve spent a lot of time reading and thinking about the First World War, and at this point descriptions of trench warfare have a visceral feel to me; I can imagine myself in the position of the soldiers on the Western Front. I get the same gut reaction, though, to Vietnam’s jungle warfare, even though I’ve spent far less time studying that conflict, because I’ve seen it in colour photographs; this still doesn’t get across the experience, obviously, but it’s much more of a “hook,” so to speak, into the subject. Yes, many photographs exist of the Great War, but colour photography has at least as much more punch to it than black-and-white photos as black-and-white photos have more than painting.

That’s changed somewhat, though, because I just recently learned that colour photographs of the First World War do exist, about 4,500 of them. That’s not a lot, relatively speaking, but I only know about them at all because I stumbled on a collection of them in a used bookstore, The First World War in Colour, by Peter Walther.

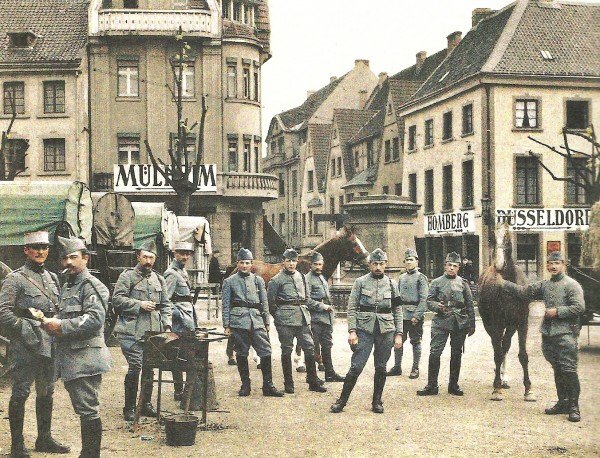

Here’s one example, taken during the Battle of the Marne:

When I first saw this, the first thing I noticed was actually the uniforms - every history of the war mentions how the French soldiers’ red pants made them easy for the Germans to spot, and now that I see them, well - no kidding.

Of course, this also just looks like a regular scene of men out camping. These men aren’t just figures in a table of troop numbers, they look like anyone I could meet today. The colour quality isn’t great, but it’s not a great deal worse than some of the commercial cameras used for a lot of my family’s photographs from well within living memory.

Speaking of uniforms that make the soldier easy to spot for the enemy:

That’s a Zouave unit; needless to say, like the main French force, they changed their uniform design fairly quickly.

Now, because of the unwieldy equipment needed and the time-consuming process of just taking these photos, there was no way to capture an ongoing battle. So, there are many images of ruins and landscapes, and all the photos of people were staged. Subjects may have been limited, but I do like the almost pedestrian quality of some of these. For example, this image of some German POWs with hand-made instruments:

One limitation I do find disappointing, though, is that the majority of these images are French. There are some photos of British forces and a few of the Germans, but almost nothing from the Eastern Front or elsewhere. This seems to have been because most of the colour photographers were French, but it would’ve been nice to have seen more of the many other armies involved in the war. I also could have gone without the photos of amputated limbs.

In any case, I’m very glad to have the book, and if you have any interest in the First World War or the history of war photography, it’s definitely worth checking out.