Third Friend: John Donne, "Holy Sonnets: Death, be not proud"

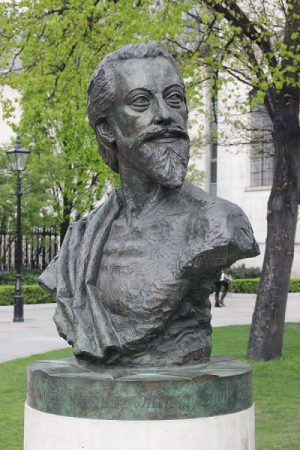

Our next acquaintance is with John Donne, who lived about a century before Alexander Pope, having been born in 1572 and passing away in 1631, and like Pope his family’s Catholic faith caused him some trouble early in his life. Interestingly, his mother was a direct descendent of St. Thomas More, and though he was able to study at Oxford and Cambridge, he couldn’t receive a degree there because his religion prevented him from swearing a required oath of allegiance to Queen Elizabeth. Unfortunately, he did not have More’s constancy, and after traveling in Italy and Spain for a few years, left the Church and became an Anglican sometime while working as a secretary for Sir Thomas Egerton. Disappointing, but I won’t doubt his sincerity given his reputation among those who knew him. He would eventually join the Anglican priesthood, despite feeling himself unworthy, after years of urging from his friends and even from King James I. He did suffer about ten years of hardship, though, because of his relationship with Anne More, who he secretly married because he knew he wouldn’t receive her father’s permission, which in those days was career suicide. In any case, he in his own lifetime he earned a prominent reputation for his works on theology, canon law, and of course, poetry. To give an idea of the respect other poets have had for Donne, his contemporaries Ben Jonson, Thomas Carew, Richard Corbett wrote poems in his honour, as did Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Coleridge’s son, Hartley, later on - and that’s just from a quick search; doubtless more examples can be found.

As one would expect, many of his poems have a religious subject, and these seem to be what he’s best known for. I’ve chosen to memorise his sonnet “Death, be not proud.”

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell;

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

Language changes mean that the last two lines don’t rhyme anymore, but so it goes. It’s a good meditation on the ultimate powerlessness of death, and I like that it contrasts with the more common portrayal of death as final and unavoidable. I will admit that, though Donne certainly isn’t the only one to use it, I don’t care for the rest/death analogy here. “From rest and sleep […] / Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow” - I guess so? “And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well / And better than thy stroke” - they do? I do like the rest of the poem, though, and I’ve found that when I dislike something held in high esteem, as this sonnet is, the problem is sometimes, though not always, more with me than the work itself, and I just need to revisit it later. Perhaps this will be one of those cases.